Elaine Race Riot

Having returned home from the battlefields of France, African Americans fulfilled their duty as front-line soldiers throughout the First World War. Treated equally in the eyes of the French troops both on and off the battlefield, it became almost a dream for a large portion of African Americans that served. Even though a large portion of the soldiers obtained high honors from the French military, they returned to the states to once again face hostility and segregation from their white counterparts. With their experiences gained from the war, veterans and other African Americans began to stand against the status quo and protect themselves even if it meant violence. The summer-long episode of racial-based conflict followed throughout the United States as violence erupted in a multitude of places. Although called the Red Summer of 1919, confrontations between African Americans and whites continued into the fall as seen by the Elaine “Race Riot.” Before going into depth about the “riots,” it is important to understand how far back racial tensions go in the region starting with the Emancipation Proclamation and the beginning of African American sharecroppers.

Background: Slaves to Sharecroppers

Part of the Mississippi River “Black Belt,” Philips County became recognized as the capital of slavery throughout eastern Arkansas due to an agricultural-based economy. Philips County relied heavily on slave labor that the slaves outnumbered the white population in 1860, as slaves represented more than sixty-percent of the county’s population.[1]

Weighing Cotton. September 9, 2011. Photograph. US Slave. http://usslave.blogspot.com/2011/09/elaine-arkansas-race-riot-1919.html.

Because of the disparity between slave and white population, Philips County’s white plantation owners were fearful of slaves becoming organized and revolt against their rules. Despite all the hardships faced by the slave community, a change took place during the Union occupation of Philips County as the Union Generals needed the labor.

Occupying Philips County beneath the Union banner at first brought no change for the slave community. As the Union forces arrived in the county, some plantation owners fled their lands leaving their slaves and property confiscated by Union troops and later reassigned to Northern investors, who continued to rely on slave labor. [2] As the Civil War continued and labor shortages occurred, African American slaves began to negotiate with Union leaders which resulted in improved working conditions, an end to corporal punishment, and exemptions from difficult work. [3] Following the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863, now freed African Americans worked with northern whites and Union officials to better the situation, as a new system came into effect that involved leasing land to white northern that hired freed blacks to work the land. Unfortunately, the system worked out terribly as African Americans earned less money and worse off than being slaves. Despite the failure of the lease system, it remained in use as white plantation owners founded the practices that saw continuous usage after the American Civil War.

With a desire to maximize profits earned, white leasers often followed unfair labor practices that harmed the newly freed African American laborers especially in the new rights that bargained for with Union leaders. These unfair labor practices included docking pay for the day’s laborers took off or charging for the supplies used in the laborer fields. [4] Wishing to provide some sense of better conditions, the Union Army established a series of regulations that kept the plantation system; however, established a minimum monthly wage and some benefits to the freed workers. Although attempts were made to enforce the new regulations, planters argued against these new regulations which led to the Union army backing off and allowed for the establishment of prior regulations that promoted unfair labor practices. Despite the continuation of unfair labor practices, African American laborers often negotiated and would receive additional benefits due to the labor shortage in the North. However, at the end of the war, former plantation owners returned to their lands as they shared no desire to bargain. The returning plantation orders wished to return to normalcy as the control they pulled over laborers echoed back to the time of slavery.

Triggering the Elaine “Race Riot”

In 1918, the sharecroppers throughout Arkansas organized the Progressive Farmers and Household Union of America (PFHUA) to advance both the moral and intellectual interests of African Americans to become a better citizen and farmer.[5] Organized together, the African Americans formed beneath the union attempted to challenge the actions of planters, who kept their sharecroppers in debt. Although sharecroppers could quit at any time, their leave became prevented due to unwritten laws that stated laborers could not leave unless their debt became settled. As a result, planters used the law against the sharecroppers by withholding the sharecroppers’ part of the yield, therefore, forced them to purchase supplies at the planter’s plantation store. [6] With a desire to challenge the unfair actions of the planters, PFHUA decided to pool money together to hire a white law firm to sue the planters at a secret meeting at a church in Hoop Spur, a town near Elaine. Unfortunately, two sheriffs showed up to disrupt the meeting as shots traded between hired bodyguards and the police which resulted in the death of one railway special agent, W. A. Adkins, and left the other seriously wounded. In the day following the shooting, posses formed and began to attack the African American community even though those part of the exchange were not all African American.

The Elaine “Race Riot”

According to several different reports about the incident, some newspapers of the period ignored some crucial information about the beginning of the Elaine “Race Riot,” like the race of those involved in the shooting. On October 1, 1919, the Arkansas Democrat reported the party responsible for the shooting composed of two white men and one African American, and that the posse of citizens attempted to run them down and failed. [7] A reaction to a white death, a white posse from Elaine attacked several African American suspects which led to sixteen deaths.[8] Not a single white became charged with Adkin’s death as African Americans faced the brunt of the punishment. Targeted for actions performed by a single member of the community, African Americans became assaulted on sight by white posses and titled as insurrectionists.

Outnumbered by the African American community, white citizens of Philip County grew fearful of any sign of massive organization within the other’s community. Before the violence of the “race riot,” white citizens and law enforcement constantly attempted to disrupt attempts for African Americans to organize as whites attempted to disrupt or spy the special Union meetings. Despite most of the shooters being white, people believed the meeting to be the final step before a complete rebellion occurred in the small town of Elaine. According to the Southern Standard, it stated that the meeting at Hoop Spur was “… a carefully planned insurrection among a certain class of negroes, and that these plans were brought to a premature head [end] by the killing of one officer and the wounding of another at Hoop Spur.” [9] Constant fear brought the white population to arm themselves under the belief that African Americans readied to destroy their way of life. The fear became so real that newspapers reported the white community began to send their wives and children out of Elaine by train, which occurred during periods of great danger, like a war. As violence reached the town of Elaine, white men sent their wives and children to neighboring towns by train. [10] The train became the method to protect their way of life, as the men prepared for the clashes with African Americans. Furthermore, the major source of the panic occurred due to the medias’ portrayal of the event as a insurrection.

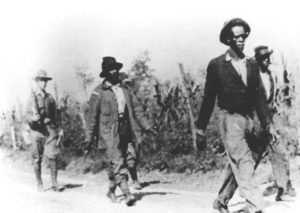

Soldiers Escorting Sharecroppers in Elaine, Arkansas 1919. September 9, 2011. Photograph. US Slave. http://usslave.blogspot.com/2011/09/elaine-arkansas-race-riot-1919.html.

A major source of information in time without any televised news, newspapers served the role of informing the public. While the events broke down across Philips county, media outlets across the United States wrote stories that described each day of the race riots, often recounting the current death tolls. Although stories differed from place to place, it came apparent that some portrayed the event differently. For instance, the Pine Bluff Daily Graphic portrayed meeting at Hoop Spur Church as a possible insurrection plot, but later reports that African American sharecroppers paid fifty dollars each for legal services at the local law offices along with papers from the PFHUA. [11] Although the article may cause more to see the event as an insurrection, at least they offer another side to the story, unlike other newspapers that discussed the event. In comparison to the Pine Bluff Daily Graphic, newspapers like the Arkansas Democrat portrayed the event as an all-out war.

Mainly centered on states involved with race riots, newspapers described events with rather graphic descriptions. As a result of these violent descriptions, it moved whites readers to react against the race riots, therefore putting the idea that people need to join and protect their way of life. For instance, the Arkansas Democrat published an article that detailed some of the fighting between a federal soldier and an armed African American that stated the following, “Corporal [Luther] Earles, while working in the round-up of the negroes in the woods near here, jumped upon a fallen log. A negro lying beside the log sprang up, fired a shotgun at the soldier, and tore off the soldier’s lower jaw. There is little chance for Corporal Luther [Earles] to recover.”[12] The description provided evoked feelings of anger towards a white reader, as they hear about the death of a veteran of the Great War by the hands of an African American that simply popped out with a shotgun. As a result of their constant imagery of violence across the county brought other whites in to clash with African Americans to revenge those killed by their hands. White citizens were not only people influenced by the panic as Governor Charles Hillman Brough accepted the fears of a posse and requested federal troops into the conflict.

After the first day of clashes between African Americans and white posses, Brough called upon five-hundred federal troops to travel from Camp Pike to Elaine. The request came out of fear as white posses reported 1,500 armed-African American men massed near the city of Elaine. A newspaper titled Pine Bluff Daily Graphic covered the story which described how a outnumber white posse requested additional reinforcements to protect the town. [13] Mainly made up of civilians, the posses pushed back a large force of 1,500 African Americans brings up whether they needed the federal troops to become involved in the situation. [14] The five-hundred troops deployed to Elaine fought in the First World War and fitted with equipment used traditionally in combat, such as approximately twelve machine gun team and high-powered rifles. [15] Upon their arrival on the second day, October 3, of the “riot,” federal troops began to bring clashed between white posses and African Americans to an end.

On the same day as their arrival, federal troops clashed with African Americans near Elaine, as conflict lasted well into the night. Reports stated that dozens of African Americans perished in the conflict with more arrested as troops made their way through the area in search of those resisting. Fearful for their lives, African Americans fled into an area called the canebrakes as soldiers pursued and surrounded the area before encountering some resistance at 10:30 PM. [16] In the short skirmish, a single African American died with another one wounded as other surrendered due to the deadly fire from the troops. [17] Although troops engaged with African Americans throughout the event, no single source points to whether the soldiers participated in the killing of the innocent, which became a subject of debate by historians and writers like Grif Stockley and Jeannie Whayne.

In February of 2002, historians Grif Stockley and Jeannie M. Whayne debated about the involvement of federal troops during the 1919 Elaine Race Riot. The debate took place at the University of Arkansas School of Law as the two debated before a moderator. Stockley started the debate with the belief that the federal troops participated in the massacre; however, all evidence was fragile. One source brought up in his argument discussed an autobiography that discussed how troops entered a company store with a captured African American to interrogate and later burn them alive. [18] The problem with the source was the author, Gerard Lambert’s All Out of Step, published the book several years after the events took place in the Elaine which left some time in between the event and the publishing of the book. Furthermore, newspapers reported that the military made a lot more arrests than the local authorities as the Chattanooga News reported more than two-hundred African Americans arrested by the military while local police arrested about sixty arrests. [19] Additionally, Wayne argued several cases where African American became grateful to see the soldiers as in one case she stated that a man hid from a white posse and hoped for the soldiers to arrive. [20] With the clashes coming to an end, the soldiers remained for several days following the events aiding in keeping the peace.

Aftermath and Conclusion

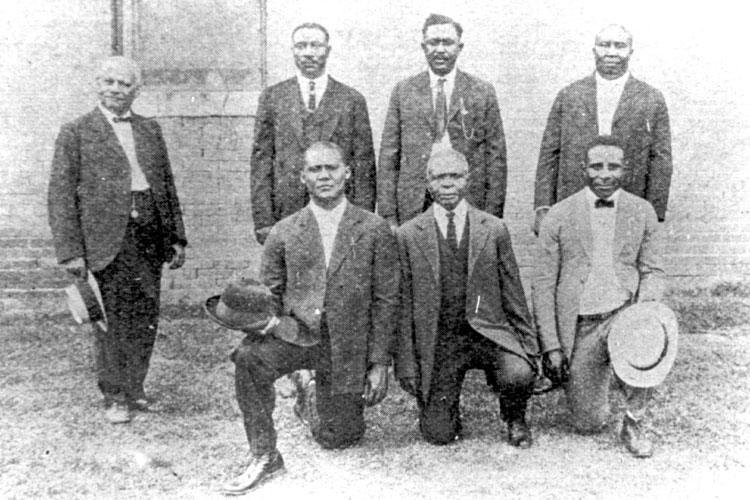

Charles H. Brough (Right) Talks with a U.S. Army Officer in the Aftermath of the Elaine Massacre; 1919. Photograph. Encyclopedia of Arkansas. Elaine, 1919. Arksansas State Archives. http://www.encyclopediaofarkansas.net/encyclopedia/media-detail.aspx?mediaID=6379

The Elaine Race Riot lasted for three days and three nights as fighting occurred between African Americans, White posses, and federal troops. Although earlier reports differed between the causalities rates, it became believed during 1919 that approximately six white men and twenty African Americans deaths resulted because of the “riots.” [21] However, historians accounted for almost over one-hundred or more unrecorded deaths because of the Elaine Race Riot. Furthermore, twelve out of sixty-five African Americans placed on trial, pleaded guilty for murder and provided death sentences by an all-white jury which later allowed the case to be sent to the United States Supreme Court after several other trails. [22] After meeting with the Supreme Court, some members of the Arkansas Twelve provided a official release by the Arkansas Court while Governor Brough furloughed others before leaving office.

Between September 30 to October 3, African American deaths totaled into the hundreds. Fueled by fear and racial superiority, Arkansas whites flocked to Elaine as reports displayed more a war-like mentality against the African American community. Furthermore, some local media outlets portrayed the initial event as a planned-revolution against the government as well as acted to protect the actions of the white posses. The addition of federal troops on October 2, both harmed and aided Elaine’s African American community as clashes between experienced troops led to higher casualties. However, the federal troops came to quell the violence as arrests became more likely towards the African American community which is displayed by African Americans willingness to rush to the troops instead of the posses. In a comparison between the six white deaths to over one-hundred African American deaths can no longer stand as a race riot, but a massacre.

Other Resources

Elaine Massacre: The Bloodiest Racial Conflict in U.S. History | Dark History | New York Post

The video is about nine-minutes in lengths and provides a in-depth and visual presentation for the Elaine Massacre. [Graphic Content]

Memorial planned to commemorate 100th anniversary of Elaine Massacre

An article from last year that spoke about a memorial created to remember the events of the Elaine Massacre.

[1] M. Langley Biegert, “Legacy of Resistance: Uncovering the History of Collective Action by Black Agricultural Workers in Central East Arkansas from the 1860s to the 1930s” Journal of Social History 32, no. 1 (1998): pp. 73-99, http://www.jstor.org/stable/3789594, 76.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ibid. 78.

[5] O. A. Rogers, “The Elaine Race Riots of 1919,” The Arkansas Historical Quarterly 19, no. 2 (1960): pp. 142-150, https://doi.org/10.2307/40025496, 144.

[6] “Elaine Race Riot,”, The Producer News, November 14, 1919, 1 edition, sec. 3, 3.

[7] Outbreak Reported at Elaine,” Arkansas Democrat, October 1, 1919, 1.

[8] Paul R. Grabiel, “4 Negroes, One White Man, Killed,” ,Arkansas Democrat, October 2, 1919, https://www.newspapers.com/image/166306657/, 1.

[9] “Race Uprising Under Control,”, Southern Standard, October 9, 1919, ,7.

[10] “Man Deaths in Arkansas Race Riot,”, The Chilicothe Constitution-Tribune, October 2, 1919, https://www.newspapers.com/image/17631372/, 1.

[11] “Three More Negroes Slain; Helena Normal; Calm Prevails,”, Pine Bluff Daily Graphic, October 4, 1919, https://www.newspapers.com/image/288941018/, 6.

[12] Paul R. Grabiel, “4 Negroes, One White Man, Killed,”, Arkansas Democrat, October 2, 1919, https://www.newspapers.com/image/166306657/, 1.

[13] “Two Whites, Seven Negroes Are Slain in Race Riot ,” ,Pine Bluff Daily Graphic, October 2, 1919, https://www.newspapers.com/image/288939442/, 6.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Grif Stockley and Jeannie M. Whayne, “Federal Troops and the Elaine Massacres: A Colloquy” The Arkansas Historical Quarterly 61, no. 3 (2002): pp. 272-283, https://doi.org/10.2307/40028029, 273.

[16] “U.S. Soldiers Ended Arkansas Race Riot,” ,The Evening Sun, October 3, 1919, https://www.newspapers.com/image/368043168/, 1.

[17] Ibid.

[18] Stockley and Whayne, “Federal Troops and the Elaine Massacre: A Colloquy,” 277.

[19] “Arkansas Wood Scene of Battle,”, The Chattanooga News, October 3, 1919, https://www.newspapers.com/image/348203420/, 1.

[20] Stockley and Whayne, “Federal Troops and the Elaine Massacre: A Colloquy,” 279.

[21] “Race Trouble Over,”, The Nashville News, October 8, 1919, https://www.newspapers.com/image/166449787/, 2.

[22] O. A. Rogers, “The Elaine Race Riots of 1919” The Arkansas Historical Quarterly 19, no. 2 (1960): pp. 142-150, https://doi.org/10.2307/40025496, 149-50.

No Comments