Eugene V. Debs Imprisoned

Eugene Victor Debs was best known as a Socialist, a labor leader, and a five time presidential candidate. In 1918, after Debs made a speech in Canton, Ohio urging people to resist the World War I draft, he was charged with sedition and sentenced to ten years in prison. Feeling as though he was wrongfully charged based on the right to free speech, Debs appealed his conviction to the Supreme Court. In Debs v. United States, the Supreme Court upheld Debs’ conviction under the Espionage Act of 1917. Debs was sent to prison on April 13, 1919 and stayed there until President Warren G. Harding commuted his sentence in December of 1921.

Before becoming the pitchman for the Socialist party, Debs was a hard worker starting at a very young age. One of ten children born of French-Alsatian immigrants, Debs left high school to begin working at the age of fourteen, mixing paints for Vandalia Railroad in his hometown Terre Haute, Indiana. After a year, the company promoted Debs to locomotive fireman. This job was extremely dangerous. One day a boiler exploded, killing two of his close friends. His mother convinced him to work at a grocery store, but he still attended firemen’s meetings and became an elected secretary at one of the lodges.

Debs quickly moved his way up the firemen’s union—the Brotherhood of Locomotive Firemen (BLF), as it was known. In 1877, he became the union’s national magazine’s editor and became secretary-treasurer three years later. With Debs in these positions, the BLF thrived, as he got the organization out of debt and claimed 8,000 members by 1883. Simultaneously while working on his union career, Debs also began a career in politics. Though he became known as a Socialist later on, his first political office was city clerk of Terra Haute, elected as a Democrat.

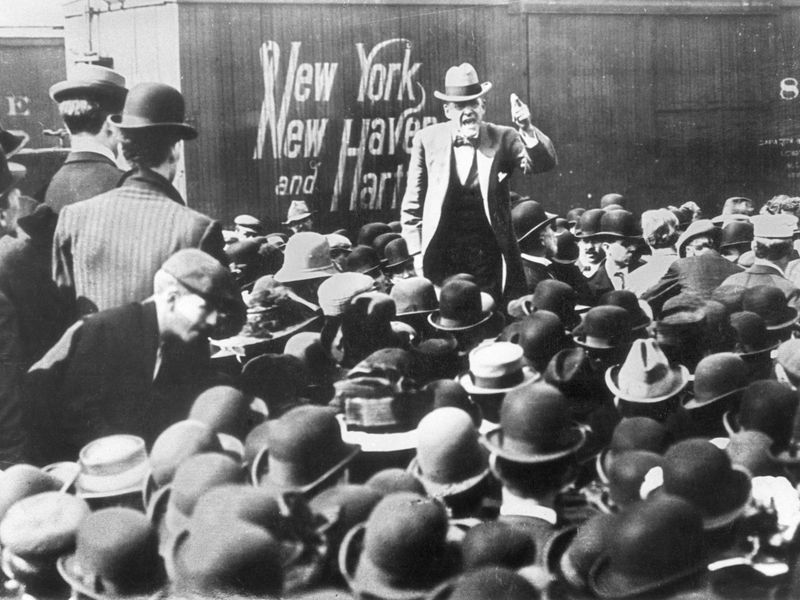

Here Debs (all the way to the right) is pictured with the Executive Board (7 of the 8 members) of the American Railway Union.

Credit: Wikipedia

Seeing that railroad brotherhoods were against the idea of integrating their craft unions into one industrial union, Debs eventually left his position at the BLF and created the American Railway Union—one of the first industrial unions of the United States. The ARU was a success. A few months after its launch, the ARU successfully pulled off an eighteen day strike, forcing the Great Northern Railroad to restore wage cuts. As a result of their victory, the union gained 150,000 within just one year.

Perhaps the most important strikes in Debs’ career to note were those against the Pullman Company. Company owner, George Pullman, decided to cut wages after the company’s revenue dropped, but kept company housing prices the same, outraging his workers. Many of these workers joined the ARU alongside Debs, who called for boycotting all trains carrying Pullman cars. However, as strikes got violent, the government, which was pro-capital and anti-union, sent the Army to stop the ARU from interfering with the train cars—the boycott completely disabled the railway system. Thus, the strike collapsed. Debs was arrested for failing to cease the boycott and sentenced to six months in prison.

It was Debs’ six month prison sentence that transformed him into a Socialist. While serving his time, Debs along with other ARU members read many pamphlets and books—Karl Marx’s Das Kapital being one of them—they received from Socialists in the United States. Debs became really interested in Socialism, to the point where he admitted he was ashamed of being a Democrat for most of his life. He received visits in jail from other Socialists, talking for hours about the Socialist cause. By the time of his release, Debs was a new man. He realized the great figure he became for unionists—he was greeted by a crowd of ten thousand when he left the prison. He delivered a speech to his supporters and urged them to use voting as a way to destroy the capitalist government. From then on, Debs became committed to Socialism and entered the next phase of his career as an American Socialist.

The first step Debs took in his career path involved dissolving the ARU to create a different organization—one that stood behind the Socialist cause. The ARU along with members of other organizations fused to become the Social Democracy of America. There would, however, be a split in the Social Democracy of America between those who favored the idea of instituting colonies to build socialism and those who preferred gaining influence through winning elections. Debs sided with the latter and formed the Social Democratic Party of America (SDP).

Debs’ first try at winning a presidential election happened in 1900. This was the first time a United States election featured a Socialist candidate. Debs, however, only received around 87,000 votes, which was about 0.6% of the votes. Though he did lose that year to Republican President William McKinley, the Socialist Party showed momentum. Debs would never win a presidential election. He ran in 1900, 1904, 1908, 1912, and 1920 while serving a prison sentence. In the decade following his first run, Debs’ votes grew each election from 0.6% to 6%—the highest amount of votes a Socialist ever received in an American presidential election—and membership of the party increased twelvefold.

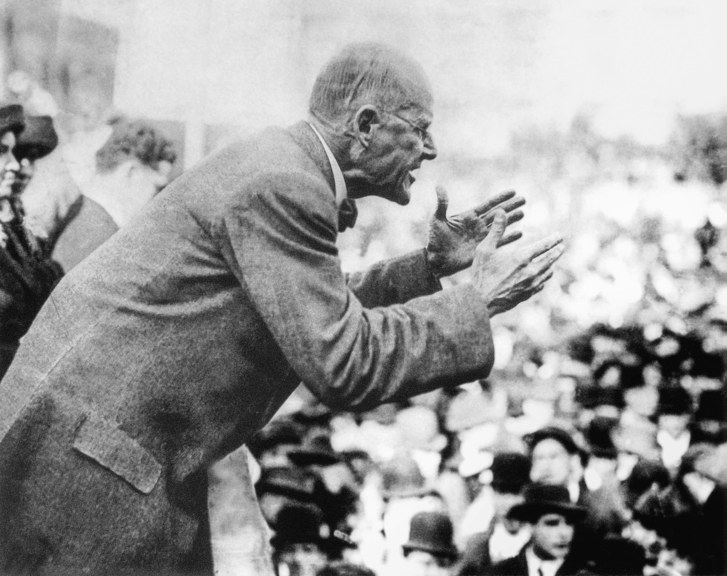

Debs campaigning for presidency before a freight-yard in 1912. As depicted in his body language, Debs was a passionate speaker.

Credit: Smithsonian Magazine

The growth that Socialism saw in the early 20th century was due to Debs’ efforts. A goal of his was to unify all Socialist parties in the United States by creating the Socialist Party of America. This unification made the Socialist Party the third biggest party by 1904. Not only did this form one bigger party of Socialists with more members, Debs speeches also attracted large crowds, contributing more conversions to Socialism. Because of his great oratory skills, many who had the chance to see Debs speak noted that his speeches were fierce and captivating, but that as a person he was kind and warmhearted. Some even referred to him as “King Debs.”

Though Debs dedicated most of his time to reform by working his way up in politics, he continued to put effort into labor unions. In 1905, he was one of the founding members of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), also known as “Wobblies.” With the growing separation between the wealthy and working class, many people were in favor of antitrust regulation, shorter work days, and child labor laws—the IWW embodied these values—and Debs saw this as an opportunity for transformation. Rather than accepting only skilled workers like the American Federation of Labor did at the time, the IWW accepted unskilled workers as well and also included workers—women, immigrants, African Americans—who most unions largely ignored. While Debs was active in the IWW during its first few years, he would eventually leave the union due to their increasingly radical tactics.

With the onset of World War One in 1914, many Socialists were vocal about opposition to the United States’ entry into the war. This included European Socialists, who felt as though they had more solidarity with workers in other countries than their own capitalist countries. Just a year prior to America’s involvement in World War One, Debs decided to run for Congress in Indiana with the goal of keeping the United States neutral. This failed as Congress declared war on Germany in April 1917. As a result, Socialists, including Debs, held anti-war rallies. In response, President Woodrow Wilson signed the Espionage Act of 1917 into law, which included lengthy prison sentences for “[w]hoever, when the United States is at war, shall willfully cause or attempt to cause insubordination, disloyalty, mutiny, or refusal of duty … or willfully obstruct the recruiting or enlistment of service of the United States.” Despite health issues Debs had at the time, he was still very vocal about his pacifism and passionate about rallying people to oppose the war as well.

The year 1917 particularly was tough for the Socialists to increase in members due to the Bolshevik Revolution that took place in Russia at the time. Many believed that Socialists developed sympathy toward the Bolshevik movement, considering Communism too had its origins in the philosophy of Marx. They also assumed that, like Russia, a Bolshevik Revolution would occur in the United States and alter the American way of life. Thus, Socialists increasingly became known as a threat by political opponents. The Wobblies, for example, were accused of plotting to establish Communism due to their radical tactics during their labor strikes. Newspapers exaggerated these kinds of political fears. The Los Angeles Times wrote in September of 1917, “The IWW conspire against the government of the United States and…every day commit actual treason…and ought to be shot as actual traitors to the country which has given them life and liberty.” Articles likes these were common to shut down the IWW and other associations tied to Socialism that the government deemed unlawful.

Debs’ outspoken opposition to America’s involvement in World War One would land him another prison sentence. Though he made numerous speeches about his views on pacifism, Socialism, and rejecting the draft, it was his speech in Canton, Ohio that got him arrested. After visiting a few anti-war Socialists in jail on June 16, 1918 who were arrested for opposing the draft, Debs delivered a speech to a party convention of 1,200 people across the street in a park. In this speech, Debs claimed that the working class made the greatest sacrifices during times of war and that they suffered while the wealthy American businessmen profited from the war. He said, “The master class has had all to gain and nothing to lose, while the subject class has had nothing to gain and all to lose—especially their lives.” Furthermore, he criticized the capitalist system, stating “To turn your back on the corrupt Republican Party and the corrupt Democratic Party—the gold-dust lackeys of the ruling class—counts for something. It counts still more…to join a minority party that has an ideal, that stands for a principle, and fights for a cause.” Debs knew he was going to jail for these words—a federal prosecutor hired a stenographer to take notes of everything Debs said during his speech.

Two weeks after his speech in Canton, Debs appeared at a Socialist picnic in Cleveland when U.S. marshals arrested him. He was charged with ten counts of violating the Espionage Act of 1917 and the Sedition Act of 1918. During his first trial, his defense called no witnesses, but instead asked that Debs be allowed to defend himself by addressing the court. Debs spoke for two hours. He admitted his guilt, saying, “I admit it. I abhor war. I would oppose the war if I stood alone.” He also criticized the basis of his arrest in stating, “If the Espionage Law stands, then the Constitution of the United States is dead.” Debs was found guilty on three counts, sentencing him to ten years in jail and disenfranchising him for life.

Debs appealed his case to the Supreme Court. Again, Debs’s was found guilty. In 1919, the Supreme Court ruled that Debs’ intent was to entice treason by obstructing the drafting of soldiers into the U.S. Army. Thus, Debs went to prison on April 13, 1919. Schenck v. United States was another case that year in which the Supreme Court sustained convictions restricting freedom of speech.

Public reaction to the Supreme Court’s ruling varied. Most newspapers favored his conviction. Amos Pinchot, a progressive activist, wrote in Appeal to Reason, “Eugene Debs, having made a speech opposing war, is rightfully convicted of willfully violating the enlistment section of the espionage act, and must, like a dangerous wild animal, be shut in a stone cell until death or executive clemency releases him.” The writer also insisted that, “The Debs conviction was not sustained because Debs opposed the war or obstructed recruiting, or even because he was a Socialist. It was sustained because Debs is a dangerous agitator…” On the other hand, supporters of Debs protested his conviction. In Cleveland, Charles Ruthenberg led a parade of Socialists, Communists, anarchists, and unionists in a parade to protest Debs’ imprisonment—this event broke out into what became known as the May Day Riots.

While serving his time in jail, Debs ran for president in 1920. He received 3.4% of the vote—slightly less than the 6% he received in 1912 on the Socialist ticket—he was asked to join the Communist Party, which formed the year of his imprisonment, but declined. Debs also took this time to write a series of columns, which appeared in The Bell Syndicate as well as the only book published under his name, Walls and Bars, after his death.

While running for president in jail, Debs ran as “Convict No. 9653.”

Credit: National Archives at Atlanta

Since Debs, along with many other activists of his kind, was jailed when the war was already over, this sparked an amnesty movement. This functioned as a way to release prisoners who spoke out against Word War One. President Wilson despised Debs and denied a presidential pardon when Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer suggested that Wilson release Debs due to his deteriorating health. However, the more sympathetic President Harding commuted Debs’ sentence to time served on Christmas Day of 1921. Right after leaving jail, Debs met with President Harding at the White House, who warmly welcome him. Following that, he boarded a train for his hometown Terra Haute where a crowd of 50,000 people cheered for him.

Debs remained active as a Socialist, though the Socialist Party itself decreased in popularity. For his efforts to maintain peace by protesting the war, Socialist Karl Wiik nominated Debs for a Nobel Peace Prize in 1924. He spent most of his last few years trying to recover his health, which was severely weakened by prison conditions. He was admitted to a sanitarium in Illinois, where he died of heart failure at the age of 70 in 1926.

Whether one agrees with Debs’ political stance or not, his impact on politics and worker rights is undeniable. Despite what many considered to be radical thoughts, Debs had the intention of improving the lives of all American citizens. Thus, he was proud to go to jail and stood up for what he believed in. Deb’s legacy lives on today in the organizations he founded that still stand and in the hearts of those who acknowledge and support what he accomplished in his lifetime.

References:

1. Amos, Pinchot. “Debs Sent to Prison to Protect Present System.” Appeal to Reason, April 26, 1919.

2. Buhle, Paul, & Max, Steve. Eugene V. Debs: A Graphic Biography. New York: Verso Books, 2019.

3. Gage, Beverly. The Day Wall Street Exploded: A Story of America in its First Age of Terror. New York: Oxford University Press, 2009.

4. Lens, Sidney. Radicalism in America. New York: Crowell, 1969.

5. Murray, Robert K. Red Scare: A Study in National Hysteria, 1919-1920. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1955.

6. Salvatore, Nick. Eugene V. Debs: Citizen and Socialist. Illinois: University of Illinois Press, 1982.

7. “Who Are the Slackers?—What Are the Traitors?.” The Los Angeles Times, September 3, 1917.

Useful Digital Resources:

Here is an infographic showing the amount of votes Debs received for each election he participated in.

How to cite this article:

MLA: Glavan, Gloria. “Eugene V. Debs Imprisoned.” Discovering 1919, 25 Mar. 2019, http://njdigitalhistory.org/1919/eugene-v-debs-imprisoned/.

APA: Glavan, G. (2019, March 25). Eugene V. Debs Imprisoned [Blog post]. Retrieved from http://njdigitalhistory.org/1919/eugene-v-debs-imprisoned/.

Chicago: Glavan, Gloria. “Eugene V. Debs Imprisoned.” Discovering 1919 (blog), March 25, 2019, http://njdigitalhistory.org/1919/eugene-v-debs-imprisoned/.

(Note: Chicago style does NOT typically cite blog posts in the bibliography. However, if this post is significant in your research or your instructor prefers that you do cite blog posts, use the above format.)

No Comments