The Chicago Race Riots of 1919

The Chicago Race Riots of 1919 unfolded over the course of a week, starting on July 27 and lasting until August 3. By the time clashes were finally repressed and brought under some level of control, thirty-eight people, twenty-three African Americans and fifteen whites were dead, and “another 537 were injured, two-thirds of them African American” (Wikipedia). On top of that, another one thousand families, mostly African American, suddenly found themselves homeless due to looting and arson (History). These numbers made 1919’s Chicago Race Riot the worst of any of the twenty-five other Red Summer race riots that raged across America and was and remains the most destructive in Chicago history.

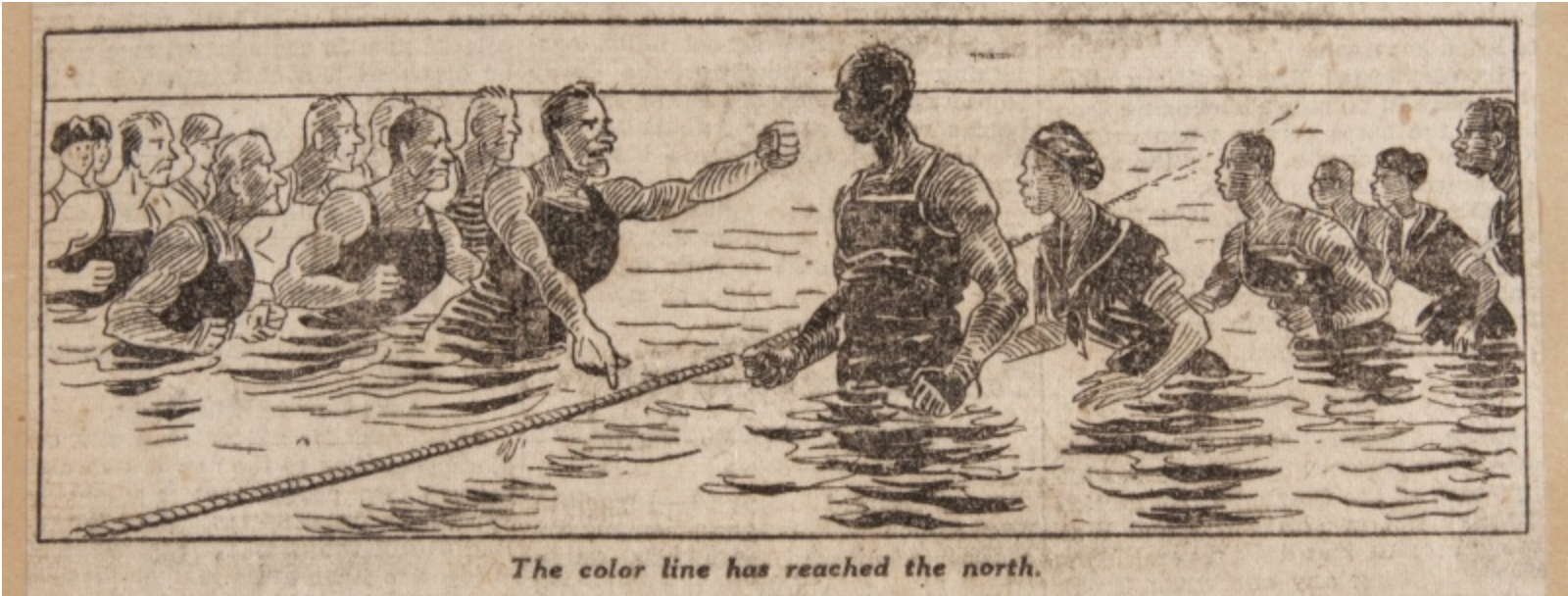

In 1919, Chicago was part of a minority of American cities that didn’t formally segregate its public spaces. However, particularly as the African American population burgeoned, spaces were “informally segregated,” governed by unspoken rules that barred African American men, women, and children from places all around the city. The South Side’s 29th Street Beach was one such place and on July 27th Eugene Williams, a black seventeen-year-old boy, who had been floating on a piece of railroad tie and drifted across the border (which was unofficial, unmarked, and arbitrarily decided upon) separating what were considered the “black beach” and the “white beach.” A white man began throwing stones at Williams, one of which hit him in the head, rendering him unable to swim and, falling from his board, he drowned soon thereafter. Upon the death, beachgoers on both the “black” and “white” beaches responded immediately and conflict quickly broke out- Williams’ friends and family were devastated and, naturally, livid over the senseless violence, while the men who threw the rock weren’t particularly apologetic, and others backed them up. This was all made exponentially worse by prejudiced police response. Fights broke out between beachgoers from the two beaches as soon as Williams drowned, but when police arrived they refused to arrest the man who’d thrown the stone. Instead, they took a black eyewitness into custody at the complaint of a white man. The story of the incident exploded and news spread at a rapid rate. Black and white mobs soon began to violently engage with one another. This conflict would rage on ceaselessly over the course of the next seven days.

Frank O. Lowden, the governor of Illinois, was not particularly quick or hands-on in his approach to dealing with the devastation; his initial response was a straight forward, fairly trite statement

“To the people of Chicago:

“I have just received notice of the appalling riots. I appeal to all citizens white and colored to

obey the law.

“There are no wrongs committed by either races that cannot be better redressed through the

orderly processes of the law than by mob violence.

“The entire power of the state will be used to restore order and punish the guilty of lawlessness.

It is a good time for all good citizens, white and colored, to aid the authorities in every way

possible to uphold the law” (Mount Carmel Item).

Ultimately though, not a lot of action came out of these words.

Chicago’s mayor at the time, William Hale Thompson, also didn’t respond very promptly as the violence became increasingly heightened. Even though the death toll was rising and the number of injured and displaced individuals and families climbed, Thompson refused to call in the National Guard until the fourth day of the riot’s seven day timeline. This, in tandem with the biased police response, allowed the riot to not only continue, but grow as crowds grew angrier and more desperate.

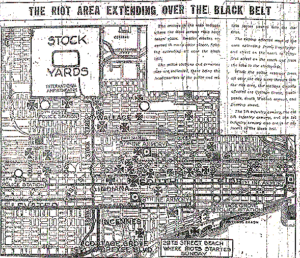

Coupled with an alarming, widespread ruthlessness, the devastation of the Chicago Race Riots was in many ways possible because of the breadth of destructive techniques were employed. Shootings, beatings, arson, and lootings occurred with no respite over the course of the week and on a large scale. From its flashpoint on the 29th Street beach, the violence tore through Chicago’s South Side and then quickly expanded beyond the “Black Belt” and into other parts of the city. The conflict grew “exceedingly bitter” and rivaled all out warfare (The Dispatch). On one night of fighting, The Dispatch, an Illinois newspaper, described a terrorized black man as an “easy victim” to beat up because he had already been “both wounded and gassed” (The Dispatch). White agitators hid along “Black Belt” roads and waited for “cars occupied by the opposite race” to pass and fire at will when the vehicle drew near (The Dispatch). Other racial offenses, such as the use of blackface by white mob members, further stoked crowds, tensions, and hate.

The historical terming of these events as “race riots” is problematic and incorrect in the connotation it attaches to the actual happenings of the time. In one way, it fails to capture the fear that the days of ruthless violence injected into the city’s South Side in particular. By July 29, the Mount Carmel Item, a Pennsylvania publication, reported

“Police stations in the negro district were filled with injured and frightened residents of the

black belt seeking protection. An overflow was cared for in city hospitals and police stations

further removed from the storm center” (Mount Carmel Item).

These “riots,” as most people, and most especially the African American population, experienced them, were not a back-and-forth clash, but an attack. Men, women, and children either felt forced to flee their homes and seek greater protection or were held up in their houses “behind drawn curtains,” trying to create separation from themselves and the horrors outside (Mount Carmel Item).

This was all coupled with an extremely biased, almost exclusively white police force. From the moment the Chicago Police were first called to the 29th Street beach, they not only repeatedly and ardently denied any and all credibility of African Americans’ reports of violence, but also demonized them, making them seem like the “bad guys” of the situation. In the midst of tumult, local newspapers were printing columns with debasing titles like “Disarming the Negro,” which framed African Americans as the enemy of Chicago, detailing “scores” of black men being arrested and each stripped of and number of “revolvers, daggers, and razors” (The Dispatch).

Further, the Chicago Race Riots were perhaps able to reach the scale that they did because of the already-existing nature of the city and the African American history that was specific to it. At the turn of the twentieth century, African Americans made up for only 1% of Chicago’s entire population. However, during the span of the two decades that followed,

this changed drastically. A renewed and growing Ku Klux Klan presence and a startling number of lynchings in the South provoked a large African American population to migrate to the northern region of the United States in what was largely called The Great Migration (or, sometimes, The Black Migration). Being located in America’s North and historically (relatively) decent toward African Americans, Chicago experienced a staggering demographic shift. In 1916, the African-American population in Chicago was 44,000, however, by 1919, it had reached 109,000- a 148% increase (Wikipedia). This population surge equated to overcrowding, most notably on the city’s South Side, which, at the time of the Migration, was predominantly composed of Irish immigrants, who were already facing similar economic hardships. When the the population began to shift, competition for already limited resources heightened and were mixed with pre-existing negative feeling between the two races that had sprung from World War I. All of this combined with the mounting national tensions of the Red Summer created an ideal climate for the Chicago Race Riots to reach the magnitude that they did.

Despite the devastation, it seemed that virtually no one was surprised by the events that took place. In fact, as the riot unfolded, newspapers reported in it more as if it were an inevitability than an eruption of tensions. Further, a number of young boys on the South Side were involved or affiliated with a “youth gang” and, many historians report evidence of these young men actually “eagerly awaiting” the racial tensions to come to a head in Chicago (Wikipedia). Though far from being the only offenders, perhaps two of the most relevant and present in this instance were the Hamburg Athletic Club and Ragen’s Colts; these groups were historically made up of mostly Irish Americans and were known to violently lash out at blacks and purposely instigate racial violence.

On August 2, as the riot still raged on, the man who had initially been accused of throwing the stone that killed Eugene Williams first appeared in Chicago Public Courts. The man, twenty-three year old George Stauber, was white and charged with murder by Chicago Detective Sergeant William Middleton, who was black. Middleton was able to bring seven eyewitnesses from the scene of Eugene Williams’ death at the 29th Street Beach to confirm that Stauber was the perpetrator. For his part, Stauber wouldn’t make and eye contact and remained silent, not making any statements in defense of the murder charge (The Daily Free Press). He was held at a $50,000 bond while the Chicago Police Department conducted a more in-depth investigation until the court adjourned once more on August 14 (The Daily Free Press). Ultimately, however, he was acquitted (Wikipedia).

At the offset of the riots, coroners began an investigation spanned seventy days and twenty nights and took into consideration the accounts of four hundred and fifty witnesses (Wikipedia). Later, Chicago government officials created the Chicago Commission on

Race Relations. Meant to function as non-partisan group, the board was made up of six white and six white men, all of whom were tasked with settling on precisely what had allowed the Chicago climate to become toxic enough to support the riots. They eventually concluded that the key sources to the city’s unrest were “competition for jobs, inadequate housing options for blacks, inconsistent law enforcement, and pervasive racial discrimination” (History).

On August 4th, directly following the end of the riots, the former president, William Howard Taft, had a letter of sorts published in newspapers, urging Americans in the direction of tolerance and sympathy. In it, he called out the widespread violence and lynchings in the South as “horrible exhibitions of blood lust” (The Washington Post). Additionally, though he didn’t go as far as promoting friendship between races, he stood by the need to at least get along or coexist without such explosive interactions. To do this, he addressed both black and white Americans and offered each with separate plans of action that, when implemented, he believed would “halt” the race riots that were occurring across the country (The Washington Post). Taft’s piece did not preach or urge equality as he did still remind white citizens that they had a “responsibility” to not be too “overweening” with their “race superiority” (The Washington Post). He does, however, freely acknowledge that whites are virtually always the instigators of these racially-charged upheavals. Though acknowledging that they were blameless, Taft, speaking directly to his black audience, insists that “direct action” would be the “worst possible remedy” to the increasingly prevalent “white outrage;” he essentially believed that the world was such that as more white men and women were killed, even more black citizens would lose their lives and, for that reason, they should try to be conservative in their defenses (The Washington Post). Nonetheless, this riot has become noted for the effect it had on black identity. Of all the large-scale racial incidents and riots of the Red Summer, it is virtually unanimously agreed that every one began with white, not black, violence (Cohen 376).

Even further, Woodrow Wilson, who was the sitting United States president in 1919, “publicly blamed whites” for inciting and propagating the Chicago Race Riots, as well as several other major incidents of the Red Summer (History). In response, Wilson introduced legislation to Congress and banded together volunteer organizations aimed at “foster[ing] racial harmony” (History). Even so, not everyone felt that this was a strong enough response from the President of the United States, particularly because he didn’t overturn federal segregation policies that he had imposed during his first term.

For more information, Clare Hartfield’s A Few Red Drops: The Chicago Race Riot of 1919 (2018) presents an in-depth look at the event from start to finish, as well as the history that preceded it and includes an array of primary sources, as well as authentic photographs and visuals from the era. This shorter video from Decades TV also summarizes the events, history, and impact of that week.

Bibliography

“Accused as Slayer.” The Daily Free Press, 2 Aug. 1919, p. 1, www.newspapers.com/image/11063398/?terms=eugene%2Bwilliams.

“Chicago Race Riot of 1919.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 4 Mar. 2019, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chicago_race_riot_of_1919.

Cohen, William. “Riots, Racism, and Hysteria: The Response of Federal Investigative Officials to the Race Riots of 1919.” The Massachusetts Review, vol. 13, no. 3, 1972, pp. 373–400. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/25088251.

“Conference of Negroes.” The Dispatch, 30 July 1919, p. 8, www.newspapers.com/image/338688798/?terms=chicago%2Brace%2Briots.

History.com Editors. “The Chicago Race Riot of 1919.” History.com, A&E Television Networks, 2 Dec. 2009, www.history.com/topics/black-history/chicago-race-riot-of-1919.

Nineteen Dead in Chicago Race Riots; Car Men Refuse Compromise and Quit Work, Mount Caramel Item July 29, 1919, p. 1

Race War Wages and Spreads to Other Districts, The Dispatch, July 30, 1919, p.8

Taft, William Howard. “Taft Says Sympathetic Aid to Negro Will Halt Rioting.” The Washington Post, 4 Aug. 1919, pp. 1–5, www.newspapers.com/image/28956557/.

No Comments