Passage of the 19th Amendment

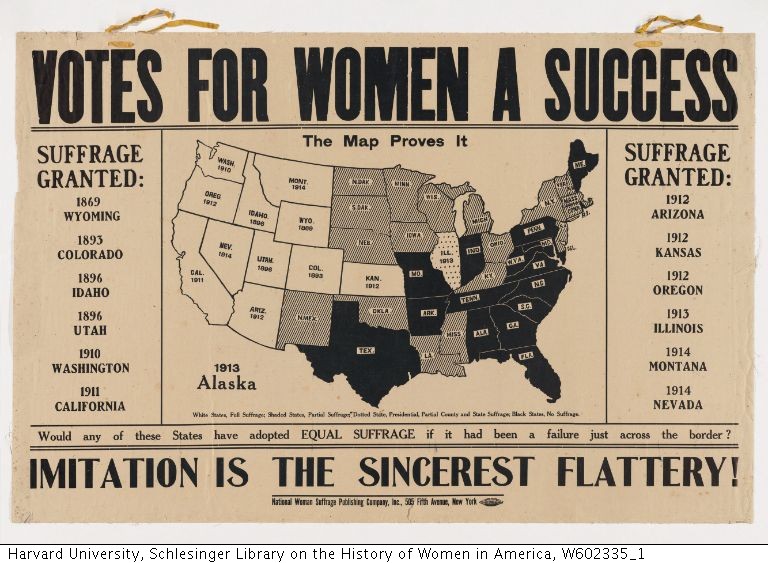

By 1919, many Western states already had the right to vote under their own state’s laws. States in that region were willing to give women the right to vote in order to attract settlers to the West. This began with the Wyoming territory and was later adopted by Utah, Colorado, and Idaho. Although there were voting rights for women in several states, the national suffrage movement did not rise to its apex until 1919. The movement originated in 1848 at the Women’s Rights Convention. The convention was followed by local, state, and national campaigns over the course of a 70-year struggle for women’s suffrage.

The suffrage movement began with organizers Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony in the

1860s. The suffragists built the National Woman Suffrage Association to organize activists and drive their movement. NWSA’s counter organization was the American Woman Suffrage Association, led by Lucy Stone. The sentiments of the organizations were similar but their execution was different. NWSA wanted the federal government to pass a new amendment, while the AWSA wanted the change in legislation to remain on a state level. Despite their differences, the two organizations merged in 1890 to form the National American Woman Suffrage Association which was taken over by Carrie Chapman Catt at the turn of the century.

Suffragists parade down Fifth Avenue, 1917.

Advocates march in October 1917, displaying placards containing the signatures of more than one million New York women demanding the vote.

The New York Times Photo Archives

The 19th Amendment was proposed for the first time in 1878 by Senator Aaron A. Sargent. The legislation was rejected leaving suffragists to extend their networks and continue their grassroots campaigns. It was not until the 1900s that the Western states had begun to give voting rights to women. The amendment was rejected in 1914 and again in 1918. In 1919, after another failed attempt earlier in the year, the amendment was finally passed by the House of Representatives and the Senate. It was then up to the states to ratify the new amendment for it to become a new addition to the constitution. In 1919, there were twenty-two states to ratify the constitution. In June, those are as follows, Illinois, Wisconsin, Michigan Kansas, Ohio New York, Pennsylvania, Massachusetts, and Texas. Iowa, Missouri, and Arkansas ratified the amendment in July. Montana and Nebraska in September. In September Minnesota, New Hampshire, and Utah ratified followed by California and Maine in November. The last states to ratify the 19th Amendment in 1919 were North Dakota, South Dakota, and Colorado. The amendment was not ratified until 1920 by Tennessee’s vote and the rest of the states follow suit that year.

The passage of the amendment was due to a combination of new tactics being deployed by the National American Woman Suffrage Association in the twentieth century. The two largest contributions to states winning women’s right to vote was the fundraising efforts and the “expediency arguments.” Suffragists were arguing that there was a need for motherhood in socio-political issues. These arguments allowed the movement to gain traction on a state level that eventually led to the passage of the 19th Amendment. In 1915 Chapman Catt created the “Winning Plan,” which called for state level laws that would enable the law’s ratification. The key points of her plan were to set up lobbyists in every state and defeat specific state Senators that opposed their cause.

Mintz, Steven. “The Passage of the Nineteenth Amendment.” OAH Magazine of History 21, no. 3 (2007): 47-50. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25162130.

Strom, Sharon Hartman. “Leadership and Tactics in the American Woman Suffrage Movement: A New Perspective from Massachusetts.” The Journal of American History 62, no. 2 (1975): 296-315. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1903256.

McCammon, Holly J., and Karen E. Campbell. “Winning the Vote in the West: The Political Successes of the Women’s Suffrage Movements, 1866-1919.” Gender and Society 15, no. 1 (2001): 55-82. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3081830.

No Comments