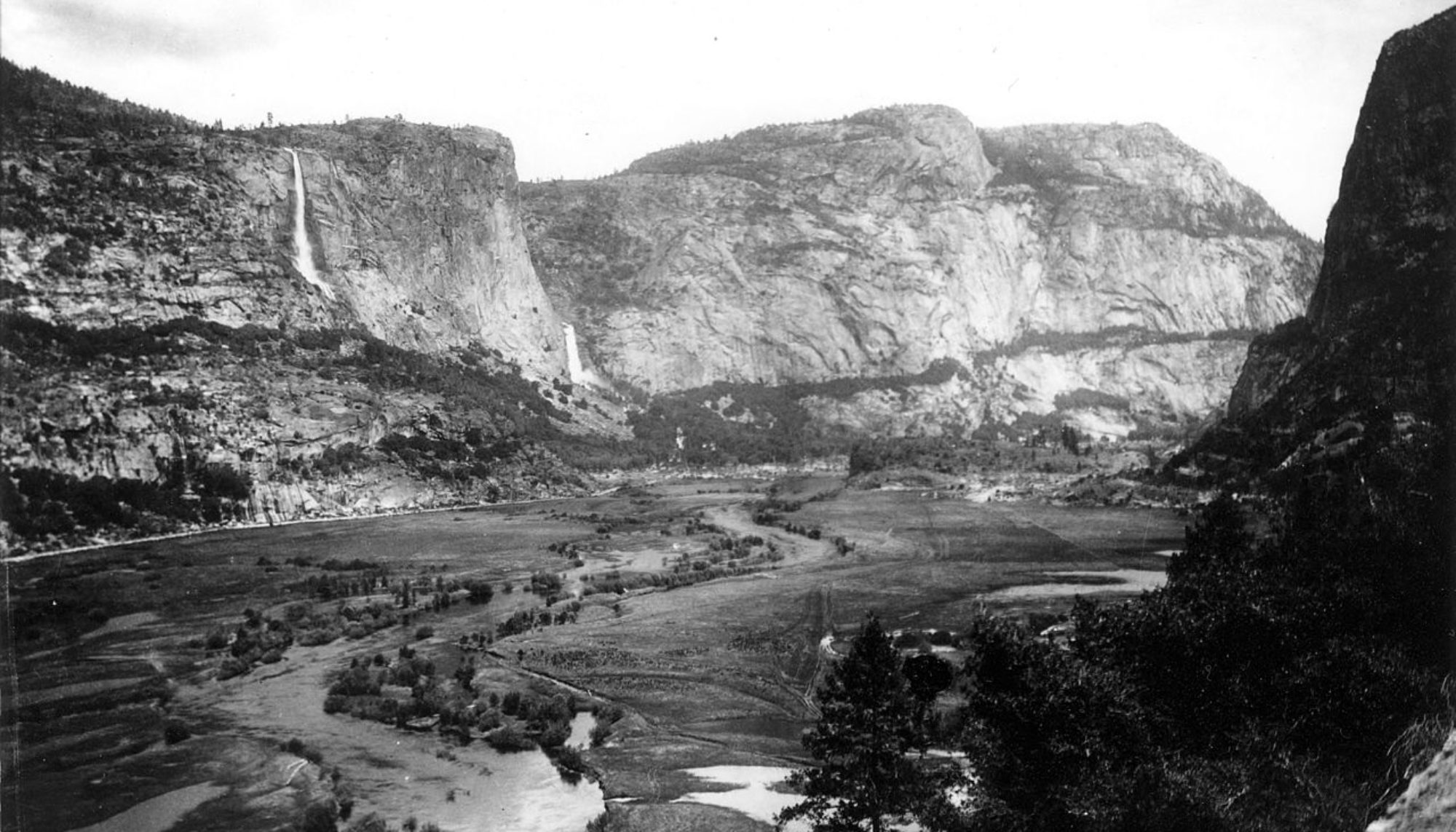

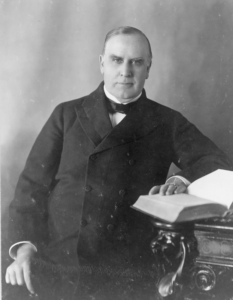

Congress established the Forest Service Organic Administration Act of 1897, or commonly known as the Organic Act, on June 30th. President William McKinley signed the bill into law. The OA was a reactionary law, created to put limitations on a presidential order issued by Grover Cleveland before leaving office in the same year. Resource industries and forestry advocates, demanding more access to the forest reserves of the West, lobbied for an amendment to the presidential order. The goals of the OA were to create and place rules, regulations, a system of management over national forest reserves, and to protect citizens access to water. Congress and members of the National Forest Commission believed that the objectives of the OA would bring order to the Forest Reserve System. Previous laws preserved national forests in their entirety, allowing for no real management of land and for only small amounts of recreation. Under the OA, the government opened up the reserves to selective logging and mining, and more recreation opportunities for the public.

The language of the Organic Act is quite extensive in detailing the changes to the Forest Reserve System it brought. (Click This LINK to Read The Full Text of The Law). From the OA, the conditions and regulations for how forests were designated, along with, access to the forests. When looking at what changes the OA brought to the system, it first needed to establish the role of a new managing body. The Department of the Interior had the task of overseeing all changes to the Reserve System and to manage the land, by the OA. The OA made stipulations that expanded the USDI’s budget, allowing them to be more effective at managing the land. Furthermore, the Secretary of the Interior had complete authority over how the day to day operations of the Forest Reserves was handled, although the organization still had to follow the rules established in Reserve legislation. The United States Geological Survey was also instrumental in the Department of the Interiors new management of the land. The USGS was responsible for the surveying and charting of all “current” and future Reserves. This ensured that all Reserve land, in the system, was properly mapped out, detailing everything and anything found in a protected forests’ borders. The USDI’s new funding and autonomy in park matters allowed for the hiring of forest rangers to manage the Reserves at the ground level. A system of management bureaucracy was starting to develop from the legislation of the OA, one that would carry on into the National Park System.

With a system of management in place, the key objects of the Organic Act could be carried out. The OA states that:

“No national forest shall be established, except to improve and protect the forest within the boundaries, or for the purpose of securing favorable conditions of water flows, and to furnish a continuous supply of timber for the use and necessities of citizens“

In the “new” forest system, for the first-time, trees that park rangers deemed were “dead,” or “matured,” and in the guidance of promoting the growth of younger trees in the reserves, were eligible to be harvested. USDI sold the rights to harvest these trees from the Reserves at a fair market price, comparable to the value of timber found outside of the said Reserve. Harvested timber had to remain in the State or Territory where acquired. However, if needed, “bona fide” settlers, residents, local industries, and, to fulfill survival needs, persons who lived near a Reserve, could apply to extract resources for free. The Secretary of the Interior had to give a permit for said people to extract resources from Reserve land. Those permitted to extract resources for free were still subject to the rules and regulations of the park in what they could take. All resources acquired from a Reserve under a permit of the Secretary of the Interior had to be used in the State or Territory where extracted. The Reserves began to be more inclusive to people in ways other than being able to extract resources from the land. Under the rules of the OA, everyone could enter the Reserves, as long as they followed posted rules. This stipulation, and a ranger service, allowed the Reserves to become tourist attractions and places people could go to enjoy nature.

FOR FURTHER CONTEXT TO THIS LAW, CLICK HERE.