Child Acting began because roles for children seemed more appropriate for children to play. Acting seems like a fun job, a creative job, but it called for long work hours, not attending school, and more. Child actors were a group affected by child labor. Working all hours of the night, this group of children were excluded from the first child welfare legislation that was enacted in Chicago around the year, 1911. Children on the stage were working all hours of the night, and as a result not attending school the next morning. How can these children learn and grow properly if they are forced to provide a paycheck for their parents? Not only does labor on the stage affect children when it comes to school, but it also exploits children: they share dressing rooms with others, change with adults, boys and girls together.

William Davis, manager of the Illinois Theater, and Mabel Taliaferro, an actress, supported the exclusion of child actors from being part of the labor laws. As a theater manager and actress, the two felt it was necessary for children to be a part of the theater. Child roles were more likable when they were performed by a child. In the Chicago Daily Tribune published on Thursday April 20, 1911, an article discussed the Child Actor bill which was debated throughout the state of Illinois. Jane Addams discussed the issues regarding children not going to school on time, falling asleep in the classroom, and staying up all hours of the night without rest.

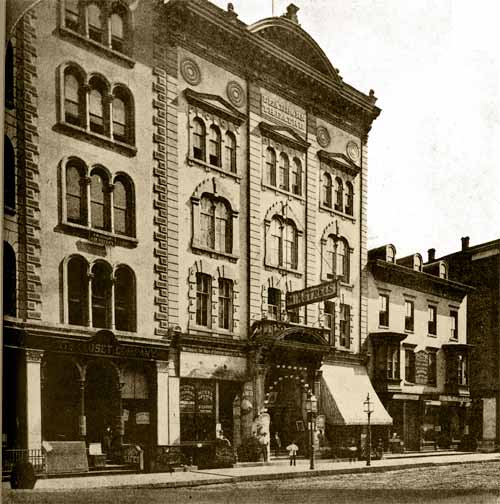

After stating the issues with excluding child actors in the bill, Addams is stated as disagreeing with the statements of those who are for the bill, “’Miss Addams, speaking before the senate committee, declared Mr. Davis was not competent to offer any evidence relating to child labor in view of the disaster in the Iroquois Theater (A safety standard for theaters and public buildings rises from the ashes of the Iroquois Theater, where more than 600 people were killed. School was out for Christmas, so the Wednesday matinee performance of “Mr. Blue Beard,” a musical starring funnyman Eddie Foy, overflowed with a standing-room audience of nearly 2,000 people, mostly women and children, at the 5-week-old Iroquois Theater. The richly appointed amusement palace on the north side of Randolph Street between State and Dearborn Streets was said to be fireproof. It would prove as unburnable as the Titanic would prove unsinkable nine years later. In the second act, as the orchestra swung into a dreamy waltz called “Let Us Swear by the Pale Moonlight,” an arc light on the left side of the stage sputtered and ignited a strip of paint-saturated muslin on a drape. Unnoticed at first by the audience, the flame ran up the strip and into the fly space above the stage where scenery hung) which occurred under his management.’” He was “incompetent” to make a statement on the matter, and frankly so was actress Mabel Taliaferro, “Because of the fact Miss Taliaferro’s moth. at one time engaged in the” booking.” of children on the stage Miss Addams said Miss Taliaferro was also incompetent to offer testimony before the committee.” How can these two people, whose opinions are less then credible be able to fight for children to be excluded from the bill? Jane Addams felt as though they were not credible and therefore the committee should have disregarded what the two of them had stated. On April 25, 1911 Addams’ testified before the Illinois State Senate committee to oppose legislation in Illinois that would exclude child actors from the state’s 1903 Child Labor Law.