The Great Molasses Flood

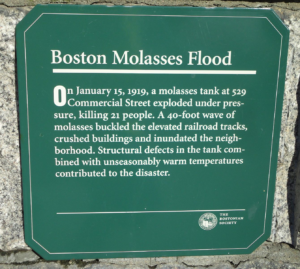

On January 15, 1919, a loud bang sounded and suddenly entire blocks of the city of Boston was swept up in a rushing wave of molasses. Four years prior, in 1915, a massive circular building, a silo of sorts, was erected in the city’s North End, housing a staggering 2,300,000 gallons of molasses for the Purity Distilling Company, a subsidiary of United States Industrial Alcohol. When the structure, which was ninety feet in diameter and stood fifty feet tall, gave out on that winter day in 1919, the results were catastrophic. A twenty-five foot wave of the thick, syrupy substance tore through the city, taking the lives of twenty-one Bostonians, ranging from ages ten to sixty-nine, and injuring one hundred and fifty more. Entire homes and businesses were swiftly swept away, completely decimated. A reported twenty-five horses also died after a Public Works Department stable was engulfed. When the molasses first settled, it was several feet high in some places. The disaster left the city in shambles and fumbling with how to begin to cleanup and rebuild from such a unique problem. Absolutely everything was sticky and coated in a layer thick and gelatinous enough to make even moving a chore.

The reason that Boston was home to such an enormous amount of molasses to begin with had nothing to do with sweetness or baking, but rather alcohol and weaponry. The need for so much of the substance and its value was heavily linked to the specific time and current events of the country. During World War I, which had ended just months before the flood, molasses gained a new importance in the United States after it was realized the the syrup could be fermented and then extracted for ethanol, a substance which is highly flammable and had become crucial in producing munitions in the war. A significant amount of the Purity Distillery Company’s molasses was shipped off to manufacturing plants and used in the production of dynamite and munitions. Molasses became doubly important in 1919 amidst a rise of Prohibition sentiments. Ethanol was also a key ingredient in alcoholic beverages, such as beer, and while this was always profitable, with a push for a national ban on the production and consumption of alcohol looming over the country, industry was ramping up production of their brews like never before, desperate to deliver their product before it was too late.

This haste pushed United States Industrial Alcohol to commission a cheap, slipshod storage tank that was rushed, built in the bitter cold, and simply never should have been. When the Great Molasses Flood first occurred the technology of the time limited Bostonians from ever fully piece in together exactly what went wrong the day of the flood, but in the past few years, science labs across the country have been tackling the particulars of the disaster. They found that climate and temperature also played major roles in this disaster. In 2014, a study was completed by the senior structural engineer of Simpson, Gumpertz & Heger, a consulting firm in Massachusetts, Ronald Mayville. In his analysis, Mayville reports that “the tank’s walls were at least 50 percent too thin and were made of a type of steel that was too brittle” (McCann). The location of the tank was specifically chosen to be in close proximity to the Boston Harbor, which made it fairly simple to get the molasses from the ships to the housing facility. Once there, the structure could reportedly hold a staggering 2.5 million gallons of molasses at any given time. That being said, in the twenty-nine times this tank had been refilled since its construction in 1915, January thirteenth was only the fourth time the vessel was filled up completely. Though this event was an absolute catastrophe, and perhaps more than anyone could have ever fathomed, there are several accounts that show that people were not particularly surprised that something went wrong with the tank. The structure reportedly used to creak, groan, and leak. Children gathered at the base of the building and collected the molasses that oozed from its delicate walls. Mayville also found that the rivet showed that at most January 15, 1919, was an unseasonably mild forty degrees Fahrenheit, a temperature that stood in stark contrast not just with a typical New England winter, but even with the day before when it had been a mere two degrees. This rapid spike in temperature likely affected fermentation processes happening inside the tank and caused an increased amount of pressure from within, something the already-tenuous structure simply could not take. Further, the molasses being stored by the Purity Distillery Company had been imported from Cuba, Puerto Rico, and the West Indies. The climates of these places, of course, stood in stark contrast to the weather of the New England city in the middle of January. The shipment that came in two days before the flood was from Puerto Rico and it is believed that even at the time of the collapse the molasses still would have been between thirty-nine and forty-one degrees (Farenheit) warmer than the current Boston air temperature -essentially concluding that the molasses “spread rapidly because it was warm from the tank, but then stiffened quickly in the cold air, impeding rescuers and costing lives” (Boston Globe). Of one couple’s North End apartment, The Boston Globe wrote

“When the crash came their tiny little home was suddenly swept across North End Park to the

middle of the field, midst a roar of crashing timbers and a deluge of seething molasses, and

dropped in a pile of wreckage and broken timbers. The roof and the floor attached to the eaves

held fast” (The Boston Globe).

The initial force of the molasses was apparently so forceful that as it first broke from the tank, a “vacuum” was created; this suction pulled in another family home and its power reduced it to nothing but a “heap” (The Boston Globe). Witnesses described that multiple other structures in the area “slid into the street” or “sucked” to the ground and, in general, all that falling timber proved to pose a significant danger not just to the people inside the buildings, but also outside in the streets, where it struck and injured or killed a number of men, women, and children, as well as work horses (Altoona Tribune).

The largest loss of life was in Boston’s city building, which was “demolished” by the wave and took the lives of numerous employees who were sitting together on their lunch break (Altoona Tribune). The city’s fire station was also destroyed by the

molasses and three fireman were killed in the tragedy.

Expanding on this, the nature of molasses and the way in which it moves has, in more recent years, become a noted point of scientific inquiry. Intensive study and research on the physics of the Great Molasses Flood took place at Harvard University, in particular, which is located in Cambridge, Massachusetts and in close proximity to the disaster’s North End flashpoint. The school has long offered an “Introduction to Fluid Dynamics” course that incorporates the Molasses Flood and the unique movement of the substance in their curriculum. In opposition to the common saying “slower than molasses,” the initial wave of molasses is estimated to have traveled at a speeding thirty-five miles per an hour. The New York Times described their process:

“The students performed experiments in a walk-in refrigerator to model how corn syrup, standing in for the molasses, would behave in cold temperatures. With that data in hand, they applied the results to a full-scale flood, projecting it over a map of the North End” (The New York Times).

Some of the Universities more intensive research on the matter is documented in this video.

Not only was the cleanup for this disaster extensive, spanning multiple city blocks, but it was also entirely unprecedented. There was no procedure in place to handle the mess covering Boston’s North End. Hundreds of Red Cross aides and city workers employed a number of varied techniques, including chisels and welds, in attempts to remove the thick, sticky, frozen molasses from every surface within blocks of the initial wreckage. The method that eventually proved to be most effective was using Boston fire boats to spray salt water in jets, the salt fairly effective in cutting through the syrup. Sand was then used to sop up as much of that water as possible. Despite these extensive efforts, Bostonians were still able to feel the stickiness of molasses “through the streets and spread it to subway platforms, to the seats inside trains and streetcars, to pay telephone handsets, into homes and to countless other places” weeks and weeks later and reports say that it was summer by the time the Boston Harbor lost the brown hue it had acquired (Wikipedia).

Since none of the detailed, extensive research available today was published until decades and decades after the actual event, finding someone liable at the time was a long and arduous process. The trial surrounding the Great Molasses Flood lasted more than five years. One hundred and nineteen lawsuits were filed against United States Industrial Alcohol and Boston residents pretty quickly filed a class-action lawsuit (a fairly new innovation at the time) against the company. The corporation asserted that the tank had been bombed by anarchists, a defense that actually held some weight. This narrative of the anarchist deviant causing havoc throughout the country was a popular one at the time of the flood and one that had enough national clout to convince, or at least scare residents pretty well. Further, with none of the knowledge and physics that Harvard was able to provide on the fluid dynamics and movement of molasses, many were skeptical that the molasses could have traveled as quickly as it did without some sort of external force (i.e. a bomb) pushing and propelling it. Over the course of the trial, over one thousand and five hundred pieces of evidence were presented and “some 1,000 witnesses testified including explosives experts, flood survivors and USIA employees” (Andrews). In the April of 1925, the court ordered United States Industrial Alcohol to pay a total of $628,000 for damages (today this would have been about $9.08 million) and relatives of each victim were given about $7,000 in compensation (this is about $101,000 today) (Wikipedia). The Massachusetts state auditor, Hugh W. Ogden, reported that found the true cause of the disaster was a structural failure in the tank and that United States Industrial Alcohol was wholly responsible, having made a number of errors and oversights in its creation. In the greater picture, the Great Molasses Flood and ensuing trial forced the nation to reexamine safety when it came to building construction and implement new, evolved laws and legislation regarding its standards.

The outlandish nature of this catastrophe has allowed it to be memorialized in a way that is far more flippant than an event that took the lives of twenty-one men, women, and children would typically be. “It’s a ridiculous thing to imagine, a tsunami of molasses drowning the North End of Boston, but then you look at the pictures,” Harvard Professor Shmuel M. Rubinstein was quoted saying as he conducted research on the event and this is true- the event has an almost absurdist quality to it, but that shouldn’t mitigate the devastation and tremendous loss of life. This sentiment was shared by Liz Nelson Weaver, who believes that “the fact that it tends to be turned into a ha-ha story does an incredible disservice to the people who lost their lives” (Shanahan). Nelson volunteers for the Friends of the Boston Harborwalk, a group that, among other things, has been fighting to provide visitors and community members with a more “engaging, interpretative” sign regarding the flood that once swept the Harborwalk, believing the current small plaque to be an inadequate memorial (Shanahan). The Director of Programs at the Massachusetts Historical Society, Gavin Kleespies observes the the devastating event is often “misremembered [as] something out of Willy Wonka;” his colleague, librarian Peter Drummey similarly notes that there is “this idea that this is something that is, if not comical, an industrial disaster that you can essentially have as an event suitable for children, even though there were children killed in it” (Giaimo). And there are, in fact, a surprising

number of children’s books and early readers focused on this topic. The books cite the real event, but instead of acknowledging the scope of the tragedy, use it as a fantastical backdrop to attract a young audience. Some try and put a moralistic spin on the day, trying to instill stronger character values in the child readers, while others include whimsical illustrations of people in their homes merrily riding the devastating wave.

To learn more about this event and the trial that came after it, 2003’s Dark Tide: The Great Boston Molasses Flood of 1919 by Stephen Puleo is considered by many to be one of the best researched accounted of the catastrophe.

Works Cited

Andrews, Evan. “The Great Molasses Flood of 1919.” History.com, A&E Television Networks, 13 Jan. 2017.

“Boston Marks the 100th Anniversary of the Great Molasses Flood.” Insurance Journal, 18 Jan. 2019.

Buildings Demolished and Occupants Buried in Wreckage— Firehouse Crushed, Elevated Railroad Put Out of Business, Altoona Tribune January 16, 1919, p. 1

Giaimo, Cara. “The Boston Molasses Flood Is Worth Taking Seriously.” Atlas Obscura, Atlas Obscura, 17

Jan. 2019.

“Great Molasses Flood.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 12 Apr. 2019.

McCann, Erin. “Solving a Mystery Behind the Deadly ‘Tsunami of Molasses’ of 1919.” The New York Times,

The New York Times, 20 Jan. 2018.

Shanahan, Mark. “The Great Molasses Flood of 1919: The Day Boston Was Swamped by a Deadly Wave –

The Boston Globe.” BostonGlobe.com,.

Sohn, Emily. “Why the Great Molasses Flood Was So Deadly.” History.com, A&E Television Networks, 15

Jan. 2019.

Wreckage of Elevated Structure Opposite Electric Freight Wharf On Commercial St, The Boston Globe January 16, 1919, p. 8

No Comments