How a Triple Homicide Led to Our Right to Silence

The phrase “You have a right to remain silent”, is a well known legal phrase that most Americans know today, due to its portrayal in television and movies. It was popularized by the Supreme Court decision in Miranda v. Arizona (1966), which compels law enforcement to advise you of your legal rights, if they want your statements to be upheld and used against you in court. The right to remain silent, our 5th amendment right against self incrimination, was not always as easy to exercise as it is now. And in 1919, a case changed the legal landscape on civil liberties, paving the way for Miranda v. Arizona.

On January 28th, 1919, Theodore T. Wong, Chang Hsi Hsie and Ben Sen Wu were found shot and killed in a rowhouse in Washington D.C. The men were Chinese diplomats working for the Chinese Educational Mission, which assisted and supervised Chinese students studying in the United States[2]. The Washington Herald noted, all the the victims were shot. And two of the three had their heads covered, “in accordance to an ancient Chinese custom of covering the faces of those who die an untimely death.”[1]. Police discovered that the men did not have their personal belongings taken, but the safe of the mission was tampered with. Although it was unknown whether or not any money was taken, a witness did tell them that one of the victims was in charge of the finances for the mission and had access to large sums of money[1]. So police deemed robbery as the motive. According to the Metropolitan Police Department (D.C. Police), this was the first triple murder in the history of the capital [1]. This shook the nation, and it quickly became a high profile case. The severity of this seemingly random violent act, as well as pressure from the local and federal government made the police desperate to solve it. After talking to the witness, a Chinese student who lived across the street, detectives zeroed in on a suspect. This man was reportedly the last person seen at the house before the bodies were found. Being their only suspect, the police did everything they could to try and get a confession.

Under the command of Police Superintendent Raymond Pullman, MPD detectives went to New York City with the witness, and located Ziang Sung Wan at a lodging house. Ziang Sung Wan was born in China, and was an occasional student who studied in Washington D.C. As a result, he frequented the mission for various forms of assistance [4]. Without a warrant, the detectives entered Wan’s room at the lodging house and convinced him to come back to Washington for questioning. Wan and the detectives returned to Washington and he was put in a secluded room and questioned by both Superintendent Pullman, and detectives. Wan at this time was still not officially under arrest, and he was subjected to questioning for over 5 hours. The witness was also present during questioning. After this, detectives took Wan to a hotel where he was secretly detained for another week, incommunicado. During this entire ordeal, Wan was severely ill due to the Spanish Flu, yet he was persistently under questioning. He was in constant pain and sometimes unable to speak, which the detectives took as a sign of guilt. For seven days, the police tried to coerce Wan into a confession, depriving him of water, food, and sleep until he incriminated himself or his brother, who Wan contacted for help. On the eighth day, detectives took Wan to the mission house. For over ten hours they walked him through the scene, and every piece of evidence, trying to connect him to the crime. They forced him to give explanations for every single piece of evidence present. On the ninth day, the police formally placed Wan under arrest after he confessed to killing one of the men. He was again subjected to hours of more questioning at the police station, still severely ill and without an attorney. On the tenth day, the police, unsatisfied with his statements, and took him back to the mission where he was once again questioned for several hours. On the eleventh day, Wan was formally interrogated and under the record (a stenographer was present). The next day, a severely ill Wan was read the interrogation report and asked to sign every page of it, ending the week and half of intense interrogations[5]. A severely ill and sleep deprived Ziang Sun Wan would sign off the interrogation report to end his suffering. However, without realizing it, he signed a confession to a triple murder.

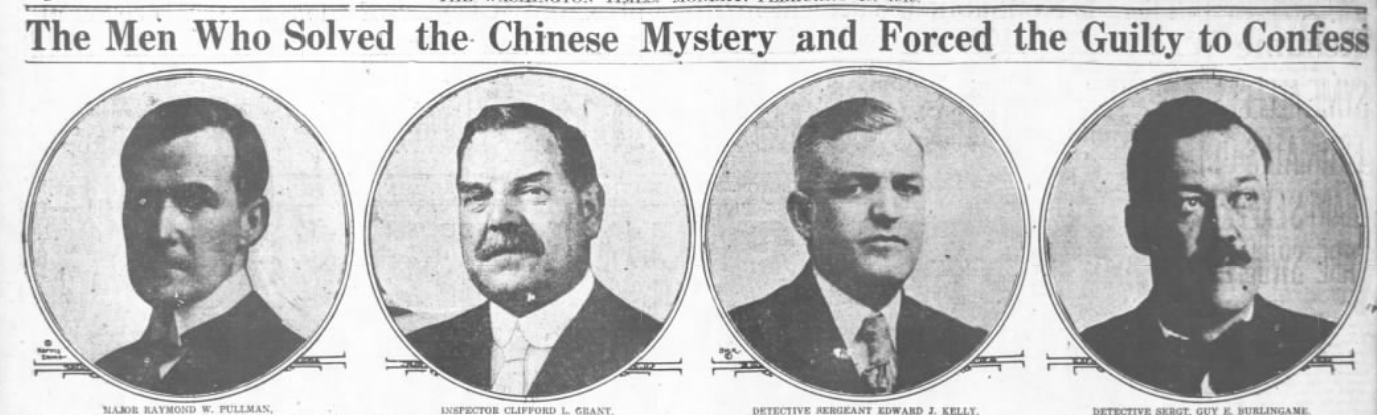

Superintendent Pullman and the lead detectives involved [Washington Times February 10, 1919 ]

Judge Louis Brandeis [Howard and Ewing Collection Library of Congress]

/https://public-media.si-cdn.com/filer/0e/83/0e83ba85-74f6-41e3-a659-bf27e0b77498/28512v.jpg)

Wan’s Trial [Library of Congress]

Learn More:

The Third Degree by Scott Seligman

Works Cited:

- 1. “Three Chinese Slain by Strange Enemy in Terrific Battle.” The Washington Herald, February 1, 1919, 4481st ed.

- 2. Ferranti, Seth, Scott Seligman. “This Brutal Triple-Murder Case Helped Establish Your Right to Remain Silent.” Vice News. May 07, 2018. Accessed February 21, 2019.

- 3. Kelly, John. “In 1919, a Triple Murder on Kalorama Road Shook Washington – and Changed the Law.” The Washington Post. September 11, 2018. Accessed February 21, 2019.

- 4. Seligman, Scott. “The Triple Homicide in D.C. That Laid the Groundwork for Americans’ Right to Remain Silent.” Smithsonian.com. April 30, 2018.

- 5. ZIANG SUNG WAN v. UNITED STATES. (October 13, 1924).

- 6. “The “Third Degree”.” Journal of the American Institute of Criminal Law and Criminology 2, no. 4 (1911): 605-07. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1133055.

Cover photo citation: Ziang Sung Wan. From the Scott Delbyk Collection

![Ziang Sung Wan [from Rob Delbyk]](https://njdigitalhistory.org/1919/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/wan.jpg)

No Comments