Volstead Act

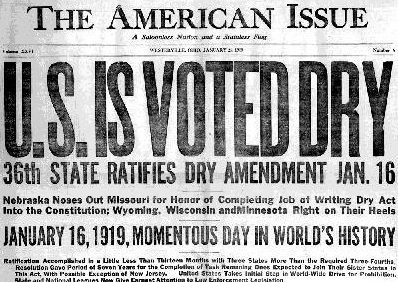

The Volstead Act, or more formally known as the National Prohibition Act, placed a nationwide constitutional ban on the sale, importation, exportation, production, and transportation of intoxicating alcoholic beverages. This was enacted to carry out the 18th Amendment that was ratified in January of 1919. The bill got its nickname Volstead after the chairman of the House Judiciary Committee, Republican Minnesota representative Andrew Volstead, who managed its legislation and advocated prohibition. On October 27, 1919, President Woodrow Wilson vetoed the bill on the grounds that it sought to enforce wartime prohibition, which ended in November of 1918, and believed it was now unnecessary. The same day he vetoed the bill, however, his veto was overridden by the House and then by the Senate the next day. On October 28, 1919, the Volstead Act became law.

Disposing illicit alcohol. Credit: New York Daily News Archive

Temperance societies had existed and advocated prohibition for many years since the early 19th century, before the 18th Amendment and the Volstead Act existed. The American Temperance Society (ATS) formed in February 1826, beginning the first organized temperance movement in America. Within ten years, over one million people pledged to stop drinking liquor with the ATS. The Anti-Saloon League was another effective organization, and its leader Wayne Wheeler drafted the bill for the Volstead Act. Women were also a powerful voice behind the temperance movement. They claimed that alcohol ruined marriages and families. In the time of America’s Industrial Revolution, men often spent the little money that they made on alcohol after their long work day. Not only did women hate the fact that their husbands spent the money on alcohol rather than saving it, they also despised how it made them act, often causing their husbands to drunkenly and abusively take out their frustrations on their families. Factory owners too enjoyed the idea of prohibition, as they believed it would improve work habits and allow employees to work longer hours. Progressive reformers saw the temperance movement as a means to improve society. All of these factors and the increasing support to ban alcohol in the years prior to the 18th Amendment made ratification possible. Those who opposed the amendment included immigrants, the working class, and Democrats.

The 18th Amendment, only 111 words long, left out many important details that left the public confused. It neither defined what was considered “intoxicating liquors”, nor did it state the penalties for having it. The amendment also did not state whether alcohol could be produced for medical and religious purposes, if the use and possession of alcohol was illegal, and more. The Volstead Act, more specifically stated that any beverage over 0.5% alcohol was considered an “intoxicating liquor.” The Act, however, was over 25 pages long and difficult to interpret. In January of 1920, the New York Daily News published “do’s and don’t” to help the public understand the Act, giving advice such as,

“You may drink intoxicating liquor in your own home or in the home of a friend when you are a bona fide guest…You may buy intoxicating liquor on a bona fide medical prescription of a doctor. A pint can be bought every ten days.…You may get a permit to move liquor when you change your residence…You cannot give away or receive a bottle of liquor as a gift…You cannot display liquor signs or advertisements on your premises…”

While prohibition may have been effective at first in reducing the amount of alcohol consumed, decreasing the number of arrests for drunkenness, and making the price of alcohol rise so high that no one could afford it, society became more and more disobedient toward the law. The very law that sought to reduce crime and corruption, improve the health of its citizens, and solve social problems did the opposite. Organized crime became a huge issue during the prohibition era, as gangs took on the once legitimate business of producing and selling alcoholic beverages—also known as “bootlegging.” Enforcing the law was difficult, as not only were gangsters actually admired by the public, they were also rich enough to bribe law enforcement into letting them off the hook. Even the police took part in the illegal activity—a Chief of Police from Chicago claimed “Sixty percent of my police [were] in the bootleg business.” Anyone who was bold enough to tell higher authority about the gang’s activities faced the chances of getting killed.

At the time, alcohol was mainly accessible in speakeasies. The alcohol sold here, however, was expensive. The price of a certain beverage depended on its potency, quality, and how hard it was to smuggle. To enter a speakeasy, one had to know their secret password, or in some cases had to present a membership card. Considering there were so many people wanted access to some form alcohol during prohibition, keeping speakeasies on the low was difficult. However, similar to gangsters, the owners of speakeasies were able to pay off law enforcement in money or free alcohol. Even if one speakeasy was shut down, more sprouted due to their profitability. Nonetheless, there were too many speakeasies for the limited members of law enforcement to keep track of—in New York alone there were 32,000 of them.

Speakeasies had a great impact on American social life. Being allowed into a speakeasy expressed one’s status, even though customers varied in class. These illegal bars were very effective in breaking cultural and racial boundaries. Together, whites and blacks drank against the law. Though some speakeasies were exclusive to men, some women that were allowed into these establishments found a new identity. Flappers, as they were known, were young women that wore short, bobbed hair and revealing clothing—they were common customers of speakeasies. People became accustomed to the lifestyle of the speakeasies, as it was where they found enjoyment. Liquor-infused partying would grow in popularity throughout the 1920s because of this.

Prohibition obviously hit the alcohol industry the hardest. The number of distilleries dropped significantly. Some of those that ceased the production of alcohol beverages switched to making industrial alcohol. This, however, contributed to the increase in the consumption of industrial alcohol, which was never meant to be drunk. Bootleggers even boosted profits by cutting the amount of drinkable alcohol and adding industrial alcohol and flavoring in their mix. In redistilling industrial alcohol, bootleggers were able to remove some poisons, but some deadly denaturants, like methanol, were almost impossible to get rid of. These poisonous bootleg liquors caused many to become blind, paralyzed, and dead.

Due to the increase of crime and the fact that ignoring the law became increasingly acceptable, prohibition lost its appeal. Newspapers constantly printed stories about police raids and crime, affirming people beliefs about the negative consequences of prohibition and how its repeal would solve the nation’s social ills. By the mid-1920s, anti-prohibition organizations grew in membership. The Association Against the Prohibition Amendment (AAPA), for example, was founded in 1920 but had little support at first. The longer prohibition lasted, the more support AAPA got. In order to make a difference, the AAPA used politics for change. They supported all “wet” candidates—meaning those who were for prohibition repeal—even if they did not agree with their other policies. The AAPA also did research and created pamphlets outlining how prohibition had failed, including topics such as ineffective enforcement, the rise in organized crime, and health issues.

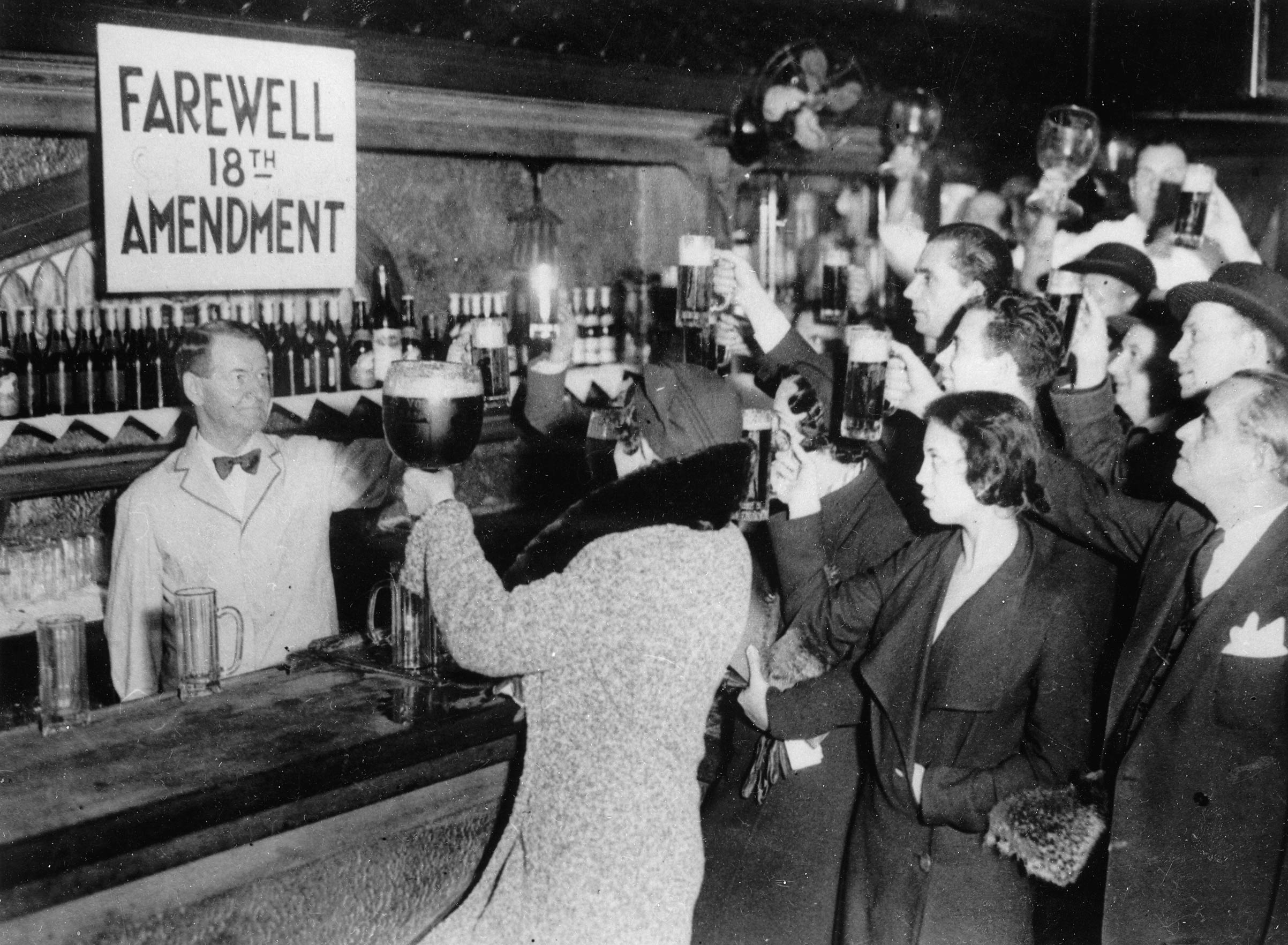

In the Presidential Election of 1932, Franklin D. Roosevelt of the Democratic Party ran on the promise that he would end prohibition and repeal the Eighteenth Amendment with a Twenty-first Amendment. President Roosevelt took office in 1933 and more likeminded wets took positions in Congress. In February of that year, Congress proposed that the Eighteenth Amendment be repealed. Then, in March, Congress passed the Cullen-Harrison Act, which legalized the sale of beer with 3.2% alcohol content, as well as wine with a similar alcohol content. It would not be until December of that year that the 36th state, Utah, ratified the Twenty-first Amendment.

The Twenty-first Amendment had two sections worth noting. First, Section 1, which repeals the Eighteenth Amendment. Then, Section 2, stating that it was illegal to import alcohol into states that still prohibited it. The control of alcohol was restored to the states. Some states did stay dry after the Twenty-first Amendment was ratified. The last state to legalized alcohol—Mississippi—did so in 1966.

Other resources:

This video shows real footage of people disposing of their alcohol and speakeasies (Credit: YouTube; Channel: Footage Direct)

A song written by Nora Bayes called “Prohibition Blues,” released in 1919 (Credit: YouTube; Channel: Nora Bayes-Topic)

References:

1. “Under the Eighteenth Amendment.” New York Daily News, January 16, 1920.

2. Blocker, Jack S., David M. Fahey, and Ian R. Tyrrell. Alcohol and Temperance in Modern History: An International Encyclopedia. California: ABC-CLIO, 2003.

3. Cherrington, Ernest H. The Evolution of Prohibition in the United States of America. Westerville: American Issue Press, 1920.

4. McGirr, Lisa. The War on Alcohol: Prohibition and the Rise of the American State. New York: W.W. Norton and Co., 2016.

5. Okrent, Daniel. Last Call: The Rise and Fall of Prohibition. New York: Scribner, 2010.

6. Spiller, John. The United States, 1763-2001. New York: Routledge, 2005.

How to cite this article:

MLA: Glavan, Gloria. “Volstead Act.” Discovering 1919, 18 Feb. 2019, http://njdigitalhistory.org/1919/volstead-act/.

APA: Glavan, G. (2019, February 18). Volstead Act [Blog post]. Retrieved from http://njdigitalhistory.org/1919/volstead-act/.

Chicago: Glavan, Gloria. “Volstead Act.” Discovering 1919 (blog), February 18, 2019, http://njdigitalhistory.org/1919/volstead-act/.

(Note: Chicago style does NOT typically cite blog posts in the bibliography. However, if this post is significant in your research or your instructor prefers that you do cite blog posts, use the above format.)

No Comments