Progressive Education Association Founded

The beginning of the twentieth century marked a sharp increase in elementary education in the United States. As it became more commonplace, it became necessary for America to reevaluate what they wanted and needed primary education to look like. In 1919, a group of well-off women working in the school system founded the Progressive Education Association (PEA) in Washington D.C. Together, they sought to steer education in a more “child-centered” direction. As it was, the classroom was not a place of discussion, or particular thoughtfulness; it was largely characterized by an “authoritarian” teacher, who passed down what they knew of “the Three Rs,” as they were known at the time- “reading, ‘riting, and ‘rithmetic” (Encyclopedia). Students were given directions on the material and were more expected to absorb it than they were to genuinely interact with it. In their John Dewey Project, the University of Vermont summarized that the goal of the pedagogy was to create “cultural uniformity, not diversity” and to form students that grew into “dutiful, not critical citizens” (University of Vermont). The Progressive Education Association sought to change this method by constructing an environment that encouraged individual thought and discourse that extended beyond “the Three Rs.”

They outlined a vision for progressive education which they summarized in the “Seven Principles of Progressive Education,” which are as follows:

- “Freedom for children to develop naturally

- Interest as the motive of all work

- Teacher as guide, not taskmaster

- Change school recordkeeping to promote the scientific study of student development

- More attention to all that affects student physical development

- School and home cooperation to meet the child’s natural interests and activities

- Progressive school as thought leader in educational movements” (Wikipedia)

As the Association began gaining more traction, a representative of the movement characterized the groups work like this

“Progressive teachers will encourage the use of all the senses, training the pupils in both

observation and judgement and, instead of hearing recitations only, will spend most of the time

teaching them how to use the various sources of information, including life activities, as well as

books” (The Baltimore Sun).

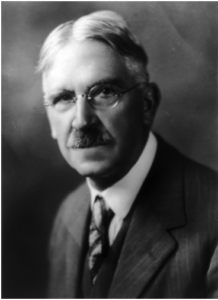

Though members and participating schools were scattered across America, Charles W. Eliot, the president of the prestigious Harvard University served as the groups’ charter president. The work done by the Progressive Education Association was not the first attempt at trying to give children greater control and freedom in their education. The PEA drew a tremendous amount of influence from philosopher John Dewey, who wrote prolifically on child-centered education and set up a string of schools implementing such philosophies in the early 1900s. As the PEA grew, Dewey was sat, for a time, as the group’s appointed president. The Chicago Laboratory School, which was founded by John Dewey, was the first school to adopt such practices and integrate them into their classrooms. Dewey further used his school as a lab for him and his colleagues to observe and improve upon their progressive theories. Students of Dewey’s eventually went on to start their own schools, all founded in the same spirit as the Chicago Laboratory School. As more schools drew more students, Dewey and his colleagues were able to draw forth a curriculum. Progressive teachers of 1919 were proud of the fact that the work the assigned had

practical use in the real world and often focused on the ways that their lessons could be bent and specified to their school’s specific geography or population. One of the early progressive schools, New York’s Lincoln School, described the implementation of the curriculum as one

“that reorganized traditional subject matter into forms embracing the development of children and the changing needs of adult life. The first and second grades carried on a study of community life in which they actually built a city. A third grade project growing out of the day-to-day life of the nearby Hudson River became one of the most celebrated units of the school” (Wikipedia contributors).

As a result of the movement teacher training and the schools that they trained at began to evolve and became more advanced and intensive. Schools like Columbia University’s Teachers College began more rigorously versing its students in scientific technique and equipping them with the tools not just to pass information to their students, but understand their psychology and foster their emotional, as well as academic, growth.

This revolution, however, was not particularly inclusive and, unfortunately, failed to acknowledge, much less address, many of the broader inequalities that plagued United States Education. Schools received exponentially better support and funding in the North than they did in the South and were much more financial capable of implementing these new techniques into their classrooms. Unlike the Northern states, the Southern states had no legislation that made education mandatory and, further, the existing classrooms, often “poorly lit and lacking indoor plumbing” with “only a few books” on hand, barely had enough money to stay open (Encyclopedia). The Progressive Education Movement also didn’t make any attempts to leverage the rampant sexism and racism in American education. Girls were far less likely than their male counterparts to finish, or sometimes even start, attending school. Classrooms were also still heavily segregated and the majority of resources were always allocated to white schools. In many ways, Progressive education and its push toward the future served only to deepen these gaps, propelling those who’d always been given the best even more stimulation and an even greater support system, while the others were simply left further and further behind.

In 1933, while attempting to summarize the movement, Frederick S. Breed of the University of Chicago framed the Progressive Education Movement as one of “reconstruction,” looking to make education more of an experience through the addition of “new qualities” and “new values” (Breed). Previously, American elementary education was structured in a way that put more value on quantity than quality; classes were made up of a greater number of children, none of whom were regularly given individualized support and things were done in one set way. With Progressive education, every student, ideally, was allowed to pursue his or her own interests within the classroom setting. Teachers were meant to be more like teammates than disciplinarians and encouraged to implement activities like reading, creative writing, and dramatics that allowed

their pupils more individual freedom. Another major concern of the group, though not directly outlined in their creido, was inclusivity. Members of the PEA worked to address mental and physical handicaps, such as blindness and deafness, and ensure that the needs of special needs students were met in elementary schools nationally. They propagated that every child in the United States had the right to benefit equally from public secondary education and, therefore, began equipping teachers with supplementary materials for students who may need additional support or a different approach to the class material. Progressive educators promoted substantial increases in governmental funding of education, which would be needed to fulfill this vision.

On March 15, 1919, the Progressive Education Association met for the first time at the Washington D.C. Public Library by the founding association members; the general public was welcome to attend. By 1930, the group had earned the respect and backing of some of the country’s most noted leaders, such as Jane Addams and began one of their largest undertakings- what became widely known as “the Eight-Year Study.” It tracked students from 30 different progressive schools with varying economic backgrounds during their college years (at any of 300 selected universities) while comparing them to students from traditional schools. Researchers found that students that had come from progressive schools were generally more involved and had an average grade point average of 2.52 compared to the 2.48 average of traditional students. When the study came to a close in the early 1940s, the commission reported that they believed that the most egregious failings of the education system were the usage of aptitude tests, which were said to be less effective than reviewing what a student had chosen to pursue during their high school years, as well as the lack of coordination that occurred between secondary schools and colleges;

Indeed, while the institution of PEA was in part an attempt to cement a distinctly “American curriculum,” its message and call for community and social interaction came at a period of social, racial, and socioeconomic strife in the United States. 1919 saw an alarming number of riots, strikes, and disaster sweep the United States, so there was something pressing about that particular time to reach out to the nation’s youth and shape a system that immediately and steadfastly instilled the values of community and collaboration into them.

Progressive education wasnot accepted without criticism. In labeling their group as “Progressive,” PEA automatically ignited a clash between themselves and conservative groups, who eschewed this new way of thinking, believing it to be non-productive. As the movement and its plans to plans to distance itself from the rote methodology of traditional education grew and spread it earned a reputation of being masterminded by the “lunatic fringe” and worthless in its technique (The Town Talk). It was criticized by parents and government officials for being primarily concerned with “finger-painting” and “sandpile studies” rather than any kind of constructive academia; in its desire to branch out, it was castigated for stripping classroom time of any practical value (The Town Talk).

The Progressive Education Association officially disbanded in 1955, but has been rebranded and rebooted several times since then. Today, a group known as the Progressive Education Network (PEN) carries on the PEA’s legacy and has been since 2005. Similar to the original Progressive Education Association they outlined their goals and vision for the group in this way:

-

“Engages students as active participants in their learning and in society.

-

Supports teachers’ voice as experienced practitioners and growth as lifelong learners

-

Builds solidarity between progressive educators in the public and private sectors

-

Advances critical dialogue on the roles of schools in a democratic society

-

Responds to contemporary issues from a progressive educational perspective

-

Welcomes families and communities as partners in children’s learning

-

Promotes diversity, equity, and justice in our schools and society

-

Encourages progressive educators to play an active role in guiding the educational vision of our society.” (PEN)

The association hosts and collaborates with teacher training programs, including a summer camp known as NIPEN that gives teachers training in giving their students a chance at have an active voice in the material that they are being given. The PEA’s work has also paved the way for the now popularized Montessori schools, which take the same progressive, child-centered approach in teaching.

Bibliography

“A Brief Overview of Progressive Education.” A Brief Overview of Progressive Education, 30 Jan. 2002, www.uvm.edu/~dewey/articles/proged.html.

Breed, Frederick S. “What Is Progressive Education?” The Elementary School Journal, vol. 34, no. 2, 1933,

- 111–117. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/995943.

Committee to Survey School Systems Here, Evening Star April 19, 1919, p. 4

“Dewey, John (1859-1952),” Jane Addams Digital Edition, accessed February 18, 2019,

https://digital.janeaddams.ramapo.edu/items/show/1872.

Lawson, Robert Frederic, and S.N. Mukerji. “Education.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia

Britannica, Inc., 29 Aug. 2018, www.britannica.com/topic/education/Progressive-education.

Palm, Reuben R. “The Origins of Progressive Education,” The Elementary School Journal, 1940 40:6,

442-449

New Methods of Education Are to Be Tried By Baltimore Women at Children’s Camp in Hills About Loch Raven, The Baltimore Sun May 18, 1919, p. 46

PEN – Progressive Education Network, progressiveeducationnetwork.org/.

Planning to Advance Progressive Education, Evening Star March 1, 1919, p. 4

“Progressive Education Association.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 27 June 2018,

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Progressive_Education_Association.

Progressive Education, The Daily Gate City and Constitution-Democrat May 9, 1919, p. 4

Schugurensky, Daniel & Natalie Aguirre. (2002). 1919: The Progressive Education Association is founded.

In Daniel Schugurensky (Ed.), History of Education: Selected Moments of the 20th Century

[online]. Available: http://fcis.oise.utoronto.ca/~daniel_schugurensky/assignment1/1919pea.html

February 16, 2019.

Study Finds ‘Progressive’ School Graduates Have Edge in College, St. Louis Post-Dispatch February 10,

1942, p. 20

“The 1910s Education: Overview.” Encyclopedia.com, Encyclopedia.com, 2019, www.encyclopedia.com/social-sciences/culture-magazines/1910s-education-overview.

Wikipedia contributors. “Progressive education.” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, 13 Apr. 2019. Web. 10 May. 2019.

I am an author working on book about Leona Sundquist, Distinguished Professor Emeritus, Western Washington University, Bellingham, WA . While at Columbia Univ in 1930-31, she was asked to write ca 2000-3000 words an “article on science teaching in progressive elementary schools for the Progressive Education Association Journal” to be printed ca September 1931.

Can you please assist me in finding this article in your archives, thank you. Arlene Sundquist-Empie

Hi Arlene, We do not have an archive– this site was built by students in my digital history course. There is an entry for the journal in WordCat that might help locate it in a library. I didn’t see any digital versions of the 1931 issue in a quick look, so interlibrary loan might be your best bet. — Cathy