Schenck v. United States

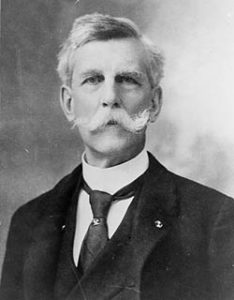

Schenck v. United States (1919) was a landmark Supreme Court case that decided that certain speech is not protected under the first amendment. The Supreme Court decided that speech was not protected if it was a “clear and present danger”, to the public or government. It was this case that Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. coined the famous example of shouting “fire!” in a crowded movie theater.

Shortly after the start of the World War I, President Woodrow Wilson started an unprecedented propaganda campaign to rally support for the war. However, Wilson and many other government leaders, had a strong sense of ethnic nationalism towards their English roots. And this sentiment started a fear of Irish, Italian, and German insurrection in the country. President Wilson said, “Any man who carries a hyphen around with him carries a dagger that he is ready to plunge into the vitals of the republic.”[7] Government propaganda made every effort to paint Germany, as well as German people, as the enemy of America. This was problematic, because the US had a large German immigrant population. The propaganda then started a chain of anti-German hysteria, and made German citizens outcasts in the United States[7]. The government promoted citizens to spy on their German neighbors and employees, report any pro-German sentiment, and this led to the unfortunate persecution of German Americans. [7].

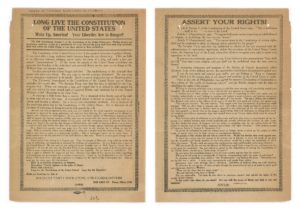

To continue with this unprecedented war effort, the United States passed the Espionage Act of 1917. The goal of the act was to prevent interference of military operations and recruitment, the promotion of government insubordination, and loyalty towards enemies of the state [2]. The act gave the United States government the power to suppress any literature or promotions they deemed advantageous to their enemies, and detrimental towards the government’s goals during the war. People arrested under this act faced a up to 20 years in prison, and up to $10,000 in fines [6] (About $200,000 in today’s money). Charles Schenck was one of the 2,100 people that were prosecuted under the Espionage and Sedition Acts [3], as well as another prominent socialist by the name of Eugene V. Debs.Charles Schenck lived in Philadelphia at the time of the case. Prior to his indictment, he was the General Secretary of the U.S Socialist Party of Philadelphia, and greatly opposed the war effort [2]. Schenck, along with fellow socialist member Elizabeth Baer, organized the mailing of 15,000 anti draft pamphlets, urging men to peacefully resist the draft. The Socialist Party of America claimed conscription was unconstitutional, as it was a violation of the 13th Amendment, which outlawed involuntary servitude and slavery [2]. Schenck’s leaflet stated, “a conscripted citizen is forced to surrender his right as a citizen and become a subject.”[4] Schenck believed that forcing citizens to serve for their country, was no different than forcing someone into servitude. When the federal government caught wind of Schenck and Baer’s activities, the and arrested for violating the Espionage Act of 1917. Schenck was convicted of three counts of violating the act, and sentenced to 10 years for each count [6]. Immediately after sentencing, Schenck and Baer appealed to the Supreme Court on the grounds that the Espionage Act violated their first amendment right to free speech [5].

Oral arguments started on Jan. 9, 1919, and Schenck’s counsel began their defense. Schenck believed that the Espionage Act was unconstitutional, because it was a clear violation of the First Amendment right to free speech. The First Amendment states, “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.” [8] Schenck argued the Espionage Act was in clear violation of this amendment, and therefore, he was free to distribute the pamphlets. The First Amendment allows citizens to vocalize and protest their concerns to the federal government, to prevent a tyranny from developing. However, the Supreme Court did not agree in this instance, and upheld Schenck’s conviction.

On March 3, 1919, the Supreme Court unanimously decided that the Espionage Act was constitutional, and that Schenck was guilty. In his opinion, Justice Wendell Oliver Holmes Jr, agreed that Schenck had a valid reason for appeal, saying, “They[Congress] set up the First Amendment to the Constitution forbidding Congress to make any law abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press, and bringing the case here on that ground have argued some other points also of which we must dispose.”[5] Furthermore, “We admit that, in many places and in ordinary times, the defendants, in saying all that was said in the circular, would have been within their constitutional rights.”[5] However, Holmes believed that the protection of free speech, depended on the time and circumstances. He famously used the example, “The most stringent protection of free speech would not protect a man in falsely shouting fire in a theatre and causing a panic.”[5] And since Schenck mailed these pamphlets with the intent of affecting the recruitment process (the Espionage Act made conspiracies criminal, not just successful attempts) during war, he was guilty under the Espionage Act. And the Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of the act with Holmes saying, “When a nation is at war, many things that might be said in time of peace are such a hindrance to its effort that their utterance will not be endured so long as men fight, and that no Court could regard them as protected by any constitutional right.” [5]

Schenck v. United was a landmark case, because it demonstrated that our rights, specifically the freedom of speech, were not absolute. The freedom of speech doesn’t protect your right to make immediate threats or state things that would cause an immediate danger to the public or the government. The clear and present danger precedent became the standard for the criminal speech, although it became more broad shortly after the decision [6]. Today we enjoy the luxury of having the

ability to speak out against any war effort. However, in 1919, the United States government was not as progressive. Fortunately, Congress repealed the Sedition Act in 1921, and the Espionage Act was left intact, but rarely used to prosecute people after World War I.

Sources:

1. “Schenck v. United States.” Oyez.

2. Waimburg, Joshua. “Schenck v. United States: Defining the Limits of Free Speech.” Constitutioncenter.org, National Constitution Center, 2 Nov. 2015

3. “The Espionage Act of 1917.” Digital History, University of Houston

4. Schenck, Charles. Long Live the Constitution of the United States. Long Live the Constitution of the United States, Socialist Party of America, 1917.

5. Schenck v. United States, 249 U.S. 47 (1919)

6. Britannica, The Editors of Encyclopaedia. “Schenck v. United States.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 24 Feb. 2019,

7. O’Malley, Michael. “Free Speech, World War One, and the Problem of Dissent.” History 120, George Mason University,

8. U.S. Constitution. Article I.

No Comments